Update time:2026-01-22Visits:3511

Profile

Zhou Qianjun is Professor and Chief Physician of Thoracic Oncology Surgery at Shanghai Chest Hospital, affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. He is also a doctoral supervisor at Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine and a recipient of the University’s prestigious “New Hundred Talents Program.”

Dr. Zhou completed postdoctoral training in immunology at the State University of New York and served as a senior visiting scholar at MD Anderson Cancer Center in the United States. In Japan, he was a visiting professor in the Department of Thoracic Surgery at Ariake Cancer Institute Hospital in Tokyo and an assistant researcher at Juntendo University’s Department of Thoracic Surgery.

He is a recipient of the 31st and 41st Sino-Japanese Sasakawa Medical Fellowship awarded by China’s Ministry of Health.

Dr. Zhou currently serves as Vice Chairman of the Sino-American Oncology Association; member of the Lung Cancer Committee of the Chinese Anti-Cancer Association; member of the Esophageal Cancer Expert Committee of the Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology; member of the Endoscopic and Robotic Surgery Branch of the Chinese Anti-Cancer Association; member of the Intelligent Equipment Technology Branch of the China Association for Medical Equipment; standing committee member of the Early Mutation and Rare Tumors Committee of the Chinese Anti-Cancer Association; standing committee member of the Tumor Heterogeneity and Personalized Therapy Committee of the Chinese Anti-Cancer Association; and standing committee member of the Tumor Marker Committee of the Chinese Anti-Cancer Association.

He also serves as Vice President of the Putuo Branch of the Shanghai Western Returned Scholars Association and as a board member of its Medical Branch.

If Medicine Were a Bridge

Open the famous Chinese scroll painting Along the River During the Qingming Festival, and one might imagine this: if medicine were the arched bridge in the painting, one side would connect to academic summits, the other to the rhythms of everyday life. A physician who stands only at the center of that bridge would miss the beauty of both shores.

For more than three decades, Zhou Qianjun has written sonnets of life inside the chest cavity with his scalpel. Lives once priced by death itself have regained the power to grow again under his hands.

“The highest calling of a physician,” he says, “is not merely repairing a broken body, but using reverence as ink to trace the shape of hope amid human suffering.”

As the tides of the Huangpu River rise and fall, his story remains a rhythm jointly written by blade and heartbeat. From laboratory benches to community alleys, he has spent thirty years living out the principle of benevolent medicine. One hand holds the sharp edge of technology to cut through disease; the other carries the candle of humanism to warm the afflicted. And along this path, he never forgets that he was once a boy clutching an admission letter, running toward medical school.

1. The Road Into Medicine

In the summer of 1991, amid the cicadas along the Huangpu River, Zhou Qianjun received his admission letter from Shanghai Second Medical University (now Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine). In that moment, he saw again the image of his father bent over medical charts — a scene that had etched itself into his childhood memory and became the starting point of his own medical journey.

“I loved sports as a kid. I competed in the Shanghai Student Games and even won a swimming championship. Once I fell while playing soccer and fractured my hand. My father simply used two splints to set it and fix it in place. A week later, I was back on the field,” Zhou recalls.

He often followed his father into hospitals, witnessing trembling hands clutching white coats, hearing muffled sobs outside operating rooms, and watching his father fashion splints for fracture patients. These early encounters planted in him a deep reverence for the word physician.

In high school, he excelled in English and hesitated between majoring in English or medicine. He ultimately entered the English-track medical program, combining both interests.

After five years of foundational study, he chose thoracic surgery for his master’s training and became a disciple of Professor Zhu Hongsheng, a pioneer of cardiothoracic surgery in China. At 31, Zhou had already become the youngest associate chief physician in thoracic surgery at Shanghai First People’s Hospital, yet he felt acutely that medicine was an endless sea of learning.

He undertook four overseas training stints but declined multiple international offers, choosing instead to return to China. After meeting Professor Luo Qingquan, whose surgical mastery profoundly impressed him, Zhou eventually joined Shanghai Chest Hospital as a recruited research talent.

From open surgery to minimally invasive thoracoscopy and then robotic-assisted precision resections, Zhou personally experienced three technological revolutions in thoracic surgery.

“In the past, open-chest surgery left a foot-long scar. Now, a few tiny incisions allow us to peel disease away thread by thread,” he says. “Behind every technological leap are countless patients who bleed less and suffer less.”

He has published over 50 papers, co-edited four monographs, and led multiple national and provincial research projects. In 2019, his team’s study on robotic-assisted segmentectomy was published in a leading international journal, opening a more precise path for early-stage lung cancer treatment.

“Saving lives is instinct. Pursuing perfection is habit,” Zhou says.

2. Innovation Creates Miracles

In the spring of 2015, a sallow-faced man stepped into Zhou Qianjun’s consultation room. His CT scans showed both lungs shrouded in shadow, with brain metastases looming like a death sentence.

“Dr. Zhou… I’m only forty-nine,” the patient said hoarsely.

Zhou paused, then replied, “Let’s try downstaging therapy.”

It was a gamble.

He initiated immunotherapy first, waiting for the tumors to recede. Then, using thoracoscopic precision, he resected the pulmonary lesions, followed by neurosurgical removal of the brain metastases. Three years later, cancer reappeared in the liver; Zhou coordinated microwave ablation with the interventional radiology team. Five years later, bone metastases struck again; he mobilized the radiation oncology department for targeted particle therapy.

Eight years later, the man—once pronounced terminal—was still alive and returning for regular follow-ups.

After his most recent checkup, he grasped Zhou’s hand, eyes reddened.

“You stitched my life into a patchwork coat,” he said. “But it holds.”

In 2019, Zhou’s team dropped what colleagues called a “depth charge” into the field: they were the first to demonstrate that circulating tumor cells detected through liquid biopsy could reliably signal early-stage lung cancer. Their findings were published in a sub-journal of The Lancet.

“We don’t just want to catch up with the global frontier,” Zhou said. “We want to lead innovation.”

The project on circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and early lung cancer diagnosis has since achieved international breakthroughs. Yet Zhou sees it only as a beginning.

“In the future, I hope we can go further in early screening and individualized treatment planning, so more patients can benefit from precision medicine.”

He has achieved similar breakthroughs in robotic surgery.

In 2022, Zhou performed China’s first domestically developed robotic lung segmentectomy. Under his control, the robotic arms moved like living creatures. Through a mere 0.8-centimeter incision, fluorescence imaging precisely outlined tumor margins.

“I used to think domestic equipment was always ‘a step behind,’” he said.

“Now we can say it with confidence: China’s intelligent manufacturing is second to none.”

Within six months, his team completed 40 such robotic procedures, using clinical outcomes to validate Chinese-made surgical systems.

3. Returning Medicine to Everyday Life

Late at night, Zhou often pauses in the corridor outside the operating theater. The glow from patient monitors blends with the distant lights of residential buildings beyond the window, forming a quiet constellation.

As surgical robots now “embroider” inside the chest cavity and AI imaging penetrates tissue to interpret lesions, Zhou has observed a paradox: the more precise medicine becomes, the wider the cognitive gap between doctors and patients.

“The battlefield of medicine shouldn’t exist only in the operating room,” he says.

“Science communication isn’t translating academic papers into plain language. It’s restoring warmth to medicine.”

In 2020, he launched a public science outreach account titled Conversations on Lung Care, addressing questions like:

“Is lung cancer caused by anger?”

“Why do square-dancing aunties have lung nodules?”

He transformed obscure medical concepts into relatable narratives—medicine boiled into what he calls “a household soup.”

As his clinical and non-clinical responsibilities multiplied, Zhou began to feel chronically short of time. To cope, he adopted ultra-fine time management, breaking his schedule into five-minute blocks.

“Only by demanding strict discipline from myself can I accomplish more—and help more patients, the public, and my students,” he says.

“Perseverance is the word that best describes my last 30 years. Everything takes time, and individual power is limited. That’s why changing yourself, persisting, and influencing others matters so much.”

4. “The Future of Thoracic Oncology Will Be Even Brighter”

To Zhou, the Department of Thoracic Oncology Surgery at Shanghai Chest Hospital is not merely a medical institution. It is a vessel carrying life, hope, and medical ambition.

“The appeal of our department lies not only in technical breakthroughs,” he says,

“but in making every patient feel the warmth of medicine—and helping every doctor find their own value.”

He believes that, after three generations of collective effort, Chinese thoracic oncology must not only catch up with international frontiers, but lead innovation in:

-minimally invasive surgery

-AI-assisted diagnostics

-precision medicine

Talent cultivation and team culture, he emphasizes, are equally critical.

“We must train doctors who are technically excellent, emotionally grounded, and innovation-driven. Behind every successful operation is a team working in perfect synchrony.”

He is equally focused on public education.

“Helping patients understand medicine is our responsibility. Our doctors use social media, short videos, and community lectures to promote thoracic health literacy.”

Technology alone is not enough.

“A hospital isn’t just a place to treat disease. It’s a place to heal the human spirit. Our department should be not only technologically advanced, but also humane—a harbor of warmth.”

At dusk along the Huangpu River, Zhou often walks alone. The horns of cargo ships and the whine of delivery scooters blend into what he calls his “dual heartbeat”:

one beating for the millimeter battles at the scalpel’s tip, the other for the warmth and hardship of ordinary lives.

ShanghaiDoctoror (Gong Zhiwei):

How do you assess China’s current level of international healthcare and its global influence?

Zhou Qianjun:

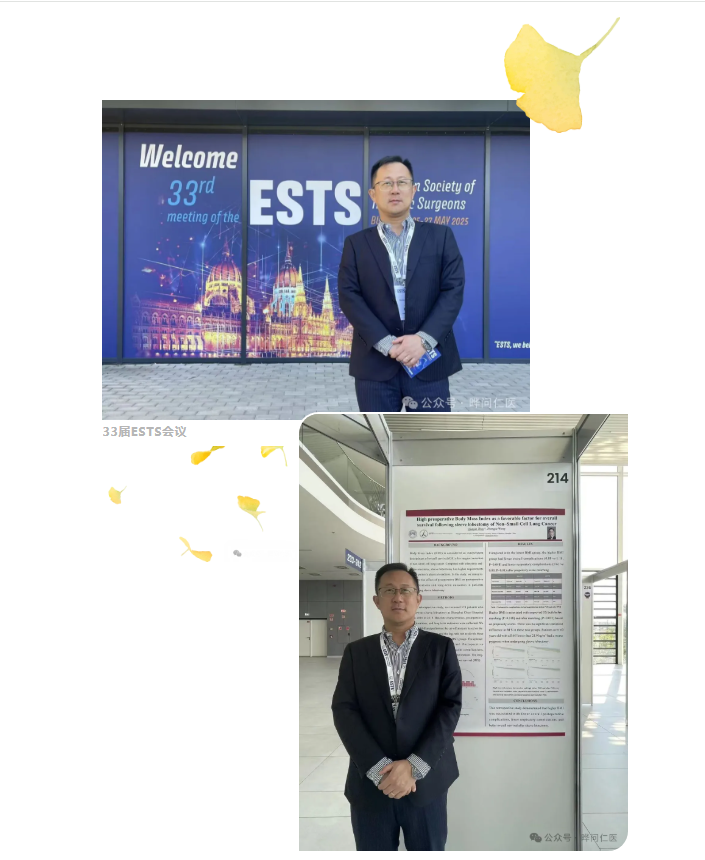

China’s healthcare system has made remarkable progress over the past decades, particularly in thoracic surgery. We are now aligned with international standards and have achieved innovation in certain areas. For example, our minimally invasive techniques and AI-assisted diagnostic systems are at the global forefront. We are also actively engaged in international academic exchange, sharing China’s experience with the world. This collaboration has strengthened our research capacity and allowed the world to witness China’s medical advancement.

ShanghaiDoctoror:

What challenges does the healthcare sector face today? How do you view the role of reputation and word-of-mouth?

Zhou Qianjun:

Healthcare challenges are multifaceted—uneven distribution of resources, limited patient understanding of medical technology, and constrained capacity to deliver optimal care.

But the greatest challenge is providing the best care with limited resources.

Word-of-mouth plays a vital role. I once treated a patient whose family found our hospital through personal referrals. He told me,

“Cure one patient, and you earn the trust of an entire village.”

That deeply resonated with me.

Medical quality is a hospital’s strongest calling card. Only by genuinely solving patients’ problems can we earn their trust and reputation.

ShanghaiDoctoror:

You’ve emphasized doctor–patient communication. Why is it so important? What role does the multidisciplinary model play?

Zhou Qianjun:

Communication is the core of healthcare.

Many patients fear their illness simply because they don’t understand it. Doctors must explain disease, treatment goals, and processes in language patients can grasp.

Multidisciplinary care is crucial here. At our hospital, surgeons and physicians collaborate closely to provide one-stop care. Patients don’t have to shuttle between departments. A joint team develops a unified treatment plan.

This model improves efficiency and gives patients a greater sense of security and trust.

ShanghaiDoctoror:

Why did you originally choose thoracic surgery? What challenges have you faced in your career?

Zhou Qianjun:

My choice was largely accidental. In my combined bachelor’s–master’s program, I selected thoracic surgery based on my academic ranking, without really understanding the field.

But once I entered it, I was deeply drawn by its intensity and sense of accomplishment.

Thoracic surgery demands extreme precision and patience. Every operation feels like a duel with death.

The greatest challenge is the pressure of complex cases.

I once treated a patient with congenital chylothorax. After three failed operations, I was close to giving up. But through team effort, we ultimately cured him. That experience reinforced my conviction.

ShanghaiDoctoror:

Outside work, what hobbies do you have? How do they help you professionally?

Zhou Qianjun:

Swimming is my greatest hobby.

Every Wednesday evening, I swim a few laps. When my body floats on the water, my mind becomes exceptionally clear. Many surgical plans and research ideas come to me while swimming.

I also enjoy reading—especially history and philosophy. These interests help me find balance in a demanding career and deepen my understanding of life and medicine.

ShanghaiDoctoror:

What advice would you give to young doctors facing the challenges of medicine?

Zhou Qianjun:

Stay curious and persevere.

Medicine evolves constantly. Young doctors must keep learning and mastering new technologies.

Don’t give up easily when facing difficulty. I once said,

“Medicine is like climbing a mountain. Stopping halfway doesn’t mean you’ve lost.”

As long as you persist, you will reach the summit.

And learn teamwork. Medical progress is never the achievement of one person—it is the product of collective effort.

Editor: Chen Qing @ShanghaiDoctor.cn

If you need any help from Dr. Zhou, Please be free to contact us at Chenqing@ShanghaiDoctor.cn