Update time:2025-10-17Visits:1806

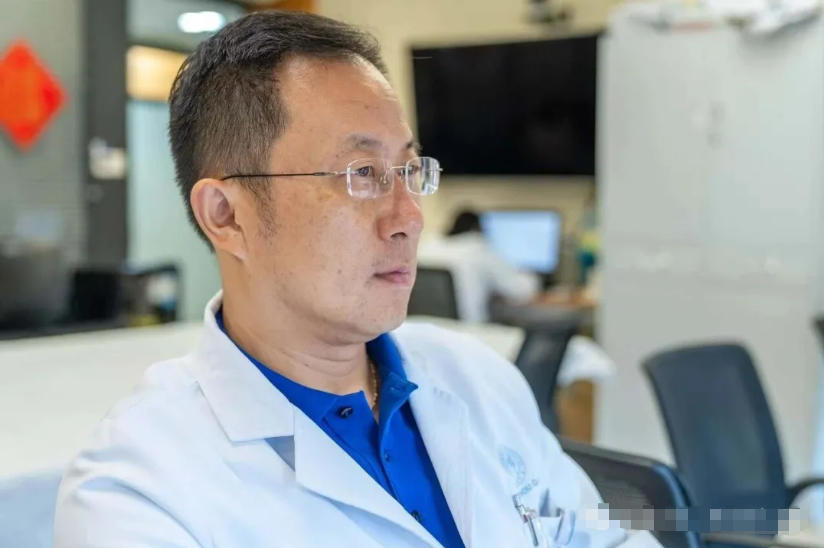

Qin Wenxin, Professor, Researcher, Doctoral Supervisor, Deputy Director of Shanghai Cancer Institute, and Deputy Director of the State Key Laboratory of Oncogenes and Related Genes.

Introduction

The journey of life, from its first bloom to its final fade, is a profound song. For QinWenxin, a biologist, understanding this song has been a lifelong passion. He is captivated by the allure of biological research—the exploration of life and the discovery of the unknown.

In the competitive field of cancer research, his work bridges the gap. He investigates the fundamental mechanisms of tumor development through basic research, translates these findings into clinical applications, and relentlessly pursues new cancer therapies.

The Path of Education

In the summer of 1981, after acing China’s national college entrance exam, QinWenxin learned he had achieved a perfect score in biology. At the time, biology was entering a renaissance, with media outlets heralding the 21st century as the “era of biology.” Seizing on this momentum, Qinenrolled without hesitation in the Department of Biology at Wuhan University.

Established in 1922, Wuhan University’s Department of Biology is one of China’s oldest and most respected modern biology programs. For a century, it has built a legacy of academic excellence and groundbreaking research, attracting pioneering faculty and dedicated students like Tan.

Qinembraced his university years with intensity. He was always the first to arrive, securing a front-row seat to absorb every lecture. The morning light on his face as he walked to class remains a vivid memory. His passion extended beyond the classroom to the laboratory, where weekly, full-day experiments allowed him to hone his meticulous observation and critical thinking skills. Evenings were spent immersed in textbooks and scientific papers, ensuring he mastered every concept.

As graduation neared, Qincontemplated his future. While the field of biology offered many paths—from agriculture to botany—he felt a calling to medicine. “After careful consideration, I decided to work at Suzhou Medical College, engaging in brain tumor research and completing my master’s degree there,” he recalls. “This was a turning point in my life.”

In 1995, shortly after earning his master’s, Qinpursued a doctorate at Shanghai Medical University. He was accepted into the lab of Academician Gu Jianren, a pioneering figure at the Shanghai Cancer Institute and one of the first academicians of the Chinese Academy of Engineering.

Academician Gu was a trailblazer, among the first scholars sent abroad to study after China’s reform and opening-up. He studied gene research at the Beatson Institute for Cancer Research in Glasgow and, upon his return, established a “State Key Laboratory” at the Shanghai Cancer Institute. Widely regarded as a founder of cancer gene and gene therapy research in China, his groundbreaking theory that “cancer is a systemic disease” has profoundly shaped the nation’s oncology landscape. “In my heart, he is not just a scholar, but my guide,” Qinsays.

Qinvividly recalls his first meeting with Academician Gu, who discussed the Human Genome Project and artificial chromosomes. Gu described a cutting-edge method for replicating artificial chromosomes in yeast cells. “To be honest, I couldn’t fully grasp it at the time; the concepts were so advanced,” Qinadmits. “But his continuous guidance on our institute’s research direction was invaluable.”

Witnessing Growth and Creating Miracles

Founded in 1958, the Shanghai Cancer Institute has long centered its research on liver cancer. Its development accelerated in the 1980s, a period when China was establishing state key laboratories to drive innovation. The institute was designated a WHO Collaborating Center for Cancer Prevention and Control in 1980 and founded the State Key Laboratory of Oncogenes and Related Genes in 1985. By 1996, it had co-established a gene therapy research base, cementing its leadership in the field.

Under Academician Gu’s leadership in the 1970s and 80s, the institute made a landmark breakthrough: the discovery and definition of the “liver cancer gene spectrum.” This theory identified seven key mutated or abnormally expressed genes linked to liver cancer, setting the agenda for future research and establishing the institute’s international reputation.

The 21st century ushered in a new era of collaboration and integration. In 2003, the institute partnered with Shanghai Jiao Tong University to form the Shanghai Jiao Tong University Cancer Institute. This evolved into a unique “institute-hospital integration” model with Renji Hospital by 2010. Under the subsequent leadership of Academician Chen Guoqiang, the State Key Laboratory continued to reach new milestones, ensuring the institute remains at the forefront of cancer research.

With more than 70 years of work, the institute has made significant strides in digestive system cancers, particularly liver cancer. “We discovered a high frequency of p53 gene mutations on chromosome 17 in liver cancer patients,” Qinexplains. “This became my doctoral project.” The p53 gene, known as the “guardian of the genome,” produces a tumor-suppressor protein that can halt cell growth or trigger cell death to prevent cancer, making it a critical focus of oncology.

Guided by Academician Gu, Qinfocused his doctoral research on identifying a specific region of deletion on chromosome 17p13.3 in liver cancer. This introduced him to advanced genomics technologies like genome sequencing and yeast artificial chromosomes (YACs). Using a YAC as a probe, Qinsuccessfully screened and sequenced 16 positive cDNA clones, which were confirmed as new human gene sequences. As first author, he published this foundational work in journals like Cell Research (2001) and Genomics (2001). These findings, later verified by institutions worldwide, provided crucial clues for cancer research and contributed to the mapping of the human genome.

After his PhD, Qinstayed at the institute to lead his own research group. For over a decade, his team focused on tumor markers. Their most significant achievement was the discovery and validation of the DKK1 (Dickkopf-1) protein in peripheral blood as a novel biomarker for liver cancer diagnosis and prognosis. As corresponding author, Qinpublished this landmark study in The Lancet Oncology. The discovery earned two U.S. and two Chinese invention patents.

As a researcher, QinWenxin remains driven by his dreams, proud to contribute his life’s work to the advancement of medicine.

From Bench to Bedside: Integrating Research and Practice

Liver cancer is a formidable global health challenge with a high mortality rate. In China, the five-year survival rate is a mere 12.1%, while in the United States, it is only slightly higher at 20.3%.

“As China has one of the highest rates of liver cancer globally, the challenges we face are particularly complex,” Qinexplains. “This forces us to focus on key problems and intensify our efforts. Our research model is to start with a clinical problem, explore it through basic science, and then translate our findings back into the clinic to solve real-world treatment difficulties.”

Since 2016, QinWenxin and his team, supported by international collaborations, have pioneered the application of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology in liver cancer research, achieving significant breakthroughs.

Compared to older technologies like ZFNs and TALENs, CRISPR-Cas9 offers distinct advantages. It is faster, more precise, and highly efficient. Its flexibility—achieved by simply altering the guide RNA sequence—allows for a wide range of applications, from gene knockouts to insertions. Moreover, its low cost and user-friendly nature have democratized gene editing.

Tan’s team has leveraged this technology to identify multiple key genes driving tumor occurrence and progression. By using CRISPR-Cas9 for large-scale functional gene screening, they can efficiently analyze the factors affecting tumor growth, metastasis, and drug resistance.

“In the past, creating gene knockouts in mouse models was time-consuming and laborious,” Qinrecalls. “With this new technology, we can work at the cellular level, systematically knocking out thousands of genes to streamline the screening process. If a particular gene is a potential target, we can identify it rapidly.”

Using CRISPR-Cas9 high-throughput screening, Tan’s team made a groundbreaking discovery: inhibiting the cell division cycle kinase 7 (CDC7) specifically induces a senescent, or dormant, state in liver cancer cells with TP53 gene mutations, while leaving normal cells unharmed. Subsequently, through high-throughput compound screening, they found that the antidepressant sertraline can selectively kill these senescent cancer cells.

This led Qinto develop a novel therapeutic strategy he calls the “one-two punch” combination therapy. The “first punch” uses a drug to exploit a specific tumor mutation, pushing cancer cells into a vulnerable state like senescence, without harming normal cells. The “second punch” is a follow-up drug designed to precisely eliminate these weakened cancer cells.

This “one-two punch” therapy has been validated in animal models, where it significantly inhibited liver cancer progression and proved more effective than existing multi-target drugs like sorafenib. This landmark research was published in the journal Nature.

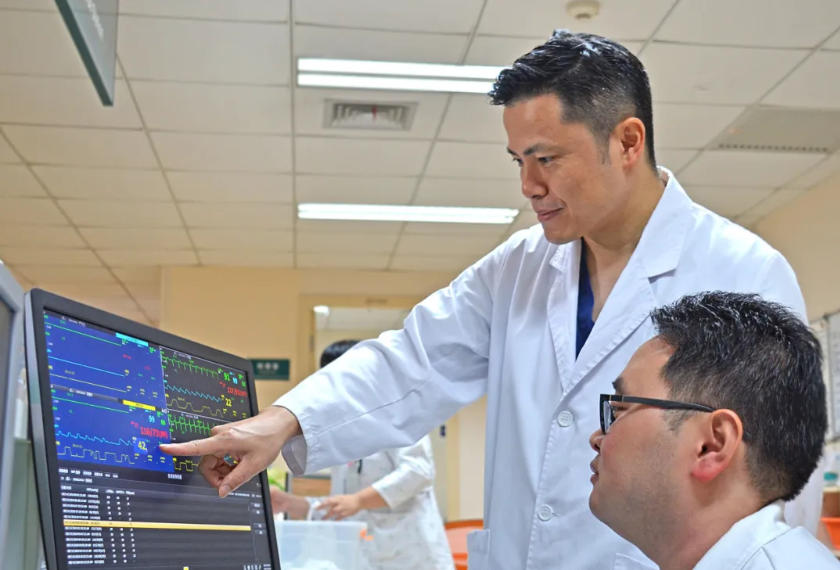

The deep integration of the Shanghai Cancer Institute and Renji Hospital creates an ideal environment for this translational research.

“Since implementing our ‘institute-hospital integration’ model, our collaboration with clinicians has become seamless,” Qinnotes. “This marks a new stage in translating research into practice. For example, in a collaboration with Director Zhai Bo’s interventional oncology team, we jointly discovered that for liver cancer patients with high EGFR expression who are insensitive to the first-line drug lenvatinib, adding an EGFR inhibitor can effectively halt disease progression.” This finding was published as a cover story in Nature, titled “Two Strikes.”

Today, this combination therapy for advanced liver cancer has advanced to clinical trials, opening new avenues for precision treatment and offering new hope to patients.

“Simply put, lenvatinib is currently effective for about 24% of liver cancer patients,” Qinexplains. “Our findings indicate that combining it with an EGFR inhibitor creates a dual-targeted therapy that could be more effective for a much broader group of patients.”

A Vision for the Future

China’s national scientific strategy, articulated as the “Four Orientations,” guides the institute’s work: facing the world’s scientific frontiers, serving the main economic battlefield, addressing the country’s major needs, and safeguarding people’s life and health. “We must align with this national strategy and focus on our research priorities,” Qinaffirms.

In Tan’s view, while basic research is the institute’s foundation, its ultimate purpose is to serve cancer patients. He believes the future of cancer control must prioritize prevention, making public health education and science communication essential.

“I once suggested incorporating cancer prevention knowledge into primary and secondary school curriculums,” he says. “Strengthening public awareness of prevention and early screening is a core strategy. Clinically, many patients are already at an advanced stage when they are first diagnosed. With active prevention and screening, about one-third of cancers could be prevented, and another third could be detected early enough for effective treatment.”

Qinalso has clear views on the future of cancer drug development.

“Looking ahead, we must not only pursue new drug targets but also deepen our understanding of existing ones to develop more effective therapies. Furthermore, since drug targets vary among patients, identifying multiple targets for combination therapy is crucial to improving treatment outcomes.”

In scientific research, talent is the most precious resource.

“Cultivating outstanding young talent is paramount for our institute’s long-term development. We must recruit and nurture the next generation of researchers. At the same time, we need to maintain a healthy, competitive awareness with other institutions worldwide, continuously strengthening our research and focusing on the forefront of cancer science.”

In the research process itself, diligence and independent thinking are vital. Researchers need a spirit of excellence, the courage to ask questions, and a willingness to think innovatively. When exploring uncharted territory, critical thinking is essential to drive continuous innovation.

“Maintaining a strong sense of curiosity is crucial; it fuels the pursuit of new knowledge and breakthroughs. China’s scientific community must place a greater emphasis on cultivating original innovation.”

The nation’s cancer research has entered a critical period, transitioning from “learning and imitation” to “original innovation.” QinWenxin looks forward to a future where China nurtures more innovative talent and produces an increasing number of original research findings, contributing significantly to global cancer prevention and treatment and benefiting patients worldwide.

Editor: Chen Qing @ ShanghaiDoctor.cn

If you'd like to contact Doctor Qin, please be free to let us know at chenqing@ShanghaiDoctor.cn.

Note: Chinese Sources from “The Path of Benevolent Medicine” which was published in 2024. It records 90 important medical figures in the history of Renji Hospital. Yewen Renyi (ShanghaiDoctor.cn) team was one of the major writers of the book and is authorized by Renji hospital to create English version on the website of ShanghaiDoctor.cn

Hospital: Renji Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine

Dr. Lei Tao | Integrating Chinese and Western Medicine, Different Paths to the Same Goal

Dr. Wang Chuanqing | Building a ‘Shield’ for Children: A Guardian Against Pathogens

Dr. Zhou Tingyin | Opening the Door to a World of Microorganism

Dr. Liang Wei | Dedicated to Vascular Health, Safeguarding the Body’s Lifelines

Dr. Zou Shien | A Physician’s Mission in Gynecological World

Dr. Bao Shihua | Where Dreams Begin from Reproductive Immunology

Dr. Yang Zhigang | The Art of the Healer: Between the Brush and the Brain

Dr. Cai Junfeng | Guarding Bone and Joint Health, Improving Quality of Life

Dr. Lei Tao | Integrating Chinese and Western Medicine, Different Paths to the Same Goal

Dr. Wang Chuanqing | Building a ‘Shield’ for Children: A Guardian Against Pathogens

Dr. Zhou Tingyin | Opening the Door to a World of Microorganism

Dr. Liang Wei | Dedicated to Vascular Health, Safeguarding the Body’s Lifelines

Dr. Zou Shien | A Physician’s Mission in Gynecological World

Dr. Cui Song | Healing the Heart, in Every Sense

Dr. Bao Shihua | Where Dreams Begin from Reproductive Immunology

Dr. Yang Zhigang | The Art of the Healer: Between the Brush and the Brain

Dr. Zhou Qianjun | Sculpting Life in the Chest

Dr. Cai Junfeng | Guarding Bone and Joint Health, Improving Quality of Life