Update time:2025-10-22Visits:2892

Professor Huang Lianjun is a leading authority in China’s field of cardiovascular imaging and interventional therapy. He is the Vice President and Director of the Department of Imaging and Interventional Therapy at Shanghai Delta Hospital. After graduating from Norman Bethune University of Medical Sciences in 1983, he worked at Fuwai Hospital and Beijing Anzhen Hospital, where he accumulated extensive clinical experience. Professor Huang specializes in the imaging diagnosis and interventional treatment of cardiovascular diseases, with outstanding achievements in treating valvular heart disease, great vessel disease, and congenital heart disease.

Introduction

Upon meeting him, one is immediately struck by his composure and rigor, which instills a sense of reassurance. He hails from the fertile black soil of China’s northeast. The footprints he left on its dirt paths marked a determined journey into medicine; the sweat he shed in the fields nurtured a seed—a desire to understand the fragility of life and alleviate the suffering of illness.

In the halls of medical school, five years of diligent study forged his commitment to healing the sick. During his internship at the prestigious Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH), the mentorship of great masters imprinted in him a profound sense of responsibility, a feeling of “treading on thin ice” with every case.

Armed with a wealth of experience, he made a decisive move from a renowned public hospital to Delta Hospital, a field of new challenges. This was a change of platform, but not a change in his healer’s mission. It was about delivering his expertise more broadly and compassionately to every patient in need.

1. The Path to Medicine

In the late 1970s, in the countryside of Nong’an County, Jilin Province, smoke curled from mud-brick houses on a chilly spring morning. This was the hometown of Huang Lianjun—a small village surrounded by vast fields and dirt roads still muddy from recent rain.

From a public broadcast speaker at the village entrance, revolutionary songs echoed, motivating villagers to embrace a new day of labor. Men and women, dressed in simple dark blue or gray cloth, carried hoes and wheelbarrows toward the fields, their faces reflecting the resilient spirit of the era.

Huang’s home was a typical farmhouse courtyard with mud-brick walls, a few fruit trees, and a vegetable patch. The furnishings were simple: a wooden table, chairs, and a heated brick bed that provided warmth for the whole family.

“My parents were simple farmers who never attended school, but they had an unwavering belief in education,” Huang said. “They always felt that ‘if you study hard, you will find a way out.’”

“A way out” was the phrase Huang heard most often. The second of four children, he was greatly encouraged when his older brother was admitted to a renowned industrial university in 1977.

“My choice to study medicine was not a romantic dream, but a practical one,” Huang explained. “For a child from the countryside, the first priority was a secure livelihood. My parents thought being a doctor meant you could support yourself and help others. That, in itself, was remarkable.”

The village’s “barefoot doctors”—paramedics who provided basic medical care in rural areas—left a deep impression on him. To this day, he remembers the image of the village doctor with a stethoscope, his earliest model of a physician. He also recalls relatives who suffered from trigeminal neuralgia and another who passed away at 40, leaving four children behind. These tragedies gave him a profound understanding of the vulnerability of rural families in the face of illness.

In 1978, Huang was admitted to the clinical medicine program at Norman Bethune University of Medical Sciences. In the following years, his younger brother and sister also passed their university entrance exams.

The five years of medical school were formative. “I underwent a great transformation,” Huang recalled. “Our university promoted the spirit of Norman Bethune, a Canadian doctor who served in China. His image and spirit were everywhere.”

“People of my generation grew up studying Chairman Mao’s ‘Old Three Articles,’ one of which was ‘In Memory of Norman Bethune,’” he said with pride. “I could recite it from a young age. To become a doctor, you had to be like Bethune—passionate about your work and constantly striving to perfect your skills.”

China had just reinstated the national college entrance exam. During his primary and secondary school years, good books were scarce. “Imagine my joy when I got to university and saw so many books. I devoured them,” Huang said with a smile. He spent most of his time in classrooms, and his academic performance consistently ranked at the top of his class.

In his fourth year, he was selected for an internship at Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH), the pinnacle of medicine in China.

“At PUMCH, I met many ‘great figures.’ I learned from them, joined them on rounds, and assisted in surgeries,” Huang recalled. He witnessed the exquisite skills and rigorous attitudes of masters like Professor Zhang Xiaoqian, Professor Chen Minzhang, and Professor Wu Zhikang.

“I remember one time, my supervising teacher and I were managing a little girl with a persistent high fever and diarrhea. Many hospitals couldn’t find the cause. When Professor Zhang came on rounds, he examined her personally from head to toe. A few minutes later, he said it might be a gastrointestinal tumor.”

Despite the limited diagnostic equipment of the time, Professor Zhang’s experience and rigorous thinking led to a quick judgment. An exploratory surgery confirmed a malignant tumor on the girl’s omentum. This shocked Huang and gave him a tangible sense of the mastery and charisma of a true physician.

PUMCH had an excellent tradition where the chief resident practically lived at the hospital. This spirit of dedication became a spiritual pillar for Huang Lianjun throughout his career.

2. A Life Transformed by Medical Imaging

Huang Lianjun’s career in medical imaging began almost by chance. Assigned to the radiology department at Beijing’s Fuwai Hospital upon graduation, he was initially reluctant. “I thought it was a peripheral specialty for underperformers,” he recalls. But a tour of the catheter lab changed everything. Seeing the cardiovascular angiography machine, a technology that seemed straight out of a movie, and learning the department was home to top experts like the esteemed Academician Liu Yuqing, he was captivated. “Just like that, my perspective changed.”

From that moment, Huang fell in love with cardiovascular imaging and interventional therapy. Fuwai Hospital was a hub of national expertise, and Huang learned from pioneers like Professor Dai Ruping, who had recently returned from abroad with advanced techniques. Professor Dai assembled a small, core team—himself, Dr. Jiang, and Huang—and they built the interventional program from the ground up. As early as 1983, this trio performed some of China’s first interventional vascular treatments, including renal artery balloon angioplasty and mitral balloon valvuloplasty.

In that era of pioneering medicine, Huang, then a resident physician, faced new cases daily with excitement and nervousness. He remembers his first independent procedure—an aortography—completing it with steady composure.

“Because Fuwai’s interventional department started so early, I may be the only doctor in China with over 42 years of continuous experience in catheter-based interventions,” Huang says. “I had the privilege of participating in many of China’s ‘firsts’ in vascular, cardiac valve, and congenital heart disease interventions. I feel a deep sense of pride in that.”

A six-month visiting scholarship at Japan’s Kumamoto University in 1994 broadened his horizons. He was struck by the open and advanced medical system. “In China, 286 computers were still rare,” he notes. “In Japan, doctors used them freely as a gateway to research.” This exposure to Japanese management and technology would profoundly influence his later work.

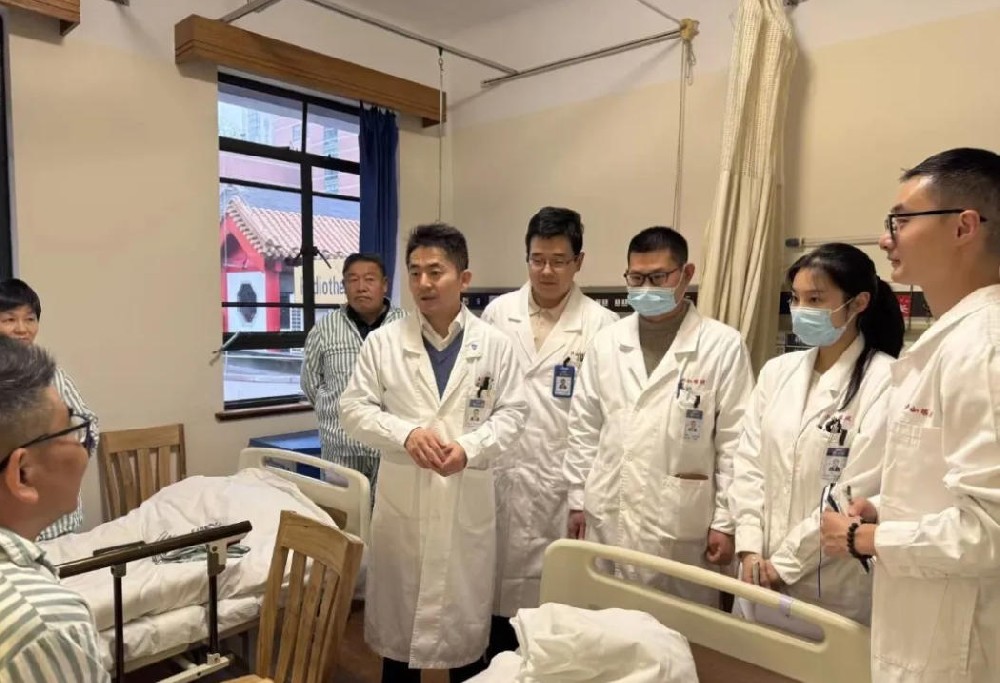

Despite their success at Fuwai, Huang and his long-time collaborator, Professor Sun Lizhong, felt they were hitting a ceiling. In 2009, they moved to Anzhen Hospital to lead its aortic disease program. Huang established an independent interventional department, leveraging Anzhen’s state-of-the-art facilities. The partnership between Huang and Sun, which began in university, was a model of collaboration. They championed a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach, one of the first of its kind in Chinese cardiovascular medicine. Huang handled imaging diagnosis and interventional therapy, while Sun managed the surgical procedures. “Whenever my intervention needed surgical backup, Professor Sun would immediately step in,” Huang explains. This seamless partnership created a comprehensive care model that attracted top talent and made Anzhen’s aortic team a national benchmark.

Huang’s philosophy is clear: “Medicine must be a passion, not just a way to make a living. You must never have ill intentions.” He advises young doctors, “Don’t be afraid of hardship. Experience is built over time, and attitude is everything.” As a leader, he prioritizes a collaborative culture: “It’s better for the whole team to be strong than for just one person to be strong.”

3. A New Frontier at Shanghai Delta Hospital

In 2014, Huang embarked on a new chapter, transitioning from public hospitals to Shanghai Delta Hospital. This was more than a job change; it was a foray into private healthcare. “Before retirement, I kept thinking about how I could contribute more,” he says. When investors approached him to build a cardiovascular center, he was cautious. “I told them running a hospital is a long-term endeavor. If the goal was just to make a quick profit, I wasn’t interested.” After several discussions, he was convinced by their patient, ten-year vision and agreed to join.

Huang also had a personal motivation. After leading programs at China’s premier institution (Fuwai) and a major regional hospital (Anzhen), he saw a new challenge. “I thought, if I could also save lives in a private hospital, wouldn’t that make my career even more complete?”

Shanghai Delta Hospital aims to serve the Yangtze River Delta region with an international standard of care. “Public resources are limited, so the private sector can supplement the market,” Huang believes. “Using private resources to serve the public is a noble cause.” He found a supportive partner in the Shanghai municipal government, which treated the private hospital as an equal, providing necessary support and autonomy. This environment allowed Delta to flourish.

Huang instilled his personal creed into Delta’s cardiovascular center. He outlines three core principles for any great physician: a good heart, refined skills, and a strong sense of responsibility. “A good heart” means building trust and empathy. “Refined skills” demand technical excellence. And “a strong sense of responsibility” is the courage to take on high-risk cases. He adds a strategic mindset: when facing a disease, “you must be confident in your overall strategy but meticulous in every tactical step.”

These principles guide Delta’s team-building. Huang recruited a core team from top public hospitals and nurtures new talent through a mentor-mentee model. The hospital fosters an open, collaborative environment with regular academic seminars. This culture extends to social responsibility; the team provides free cardiac care to children in remote regions like Sichuan and Tibet. This commitment builds trust that transcends borders. Huang recalls an Australian-Chinese patient with a complex aortic dissection who insisted on returning to China for treatment at Delta. “After her surgery, her local doctor in Australia called to say, ‘Our Chinese colleagues did an excellent job!’ That made me incredibly proud,” he says. “Not because of our technology, but because trust had crossed borders.”

Trust stems from the warmth of care and the depth of professionalism. This is the foundation upon which Huang Lianjun continues to build his legacy as a healer.

4. “There’s No Such Thing as a ‘Bad’ Doctor-Patient Relationship”

For Huang Lianjun, trust is the bridge and responsibility is the cornerstone of the doctor-patient relationship, a principle he carries with him to Shanghai Delta Hospital.

He firmly believes, “There are no unmanageable doctor-patient relationships.”

“Tensions are born from information gaps and mismatched expectations,” he explains. “The moment a patient lies on the operating table, they have placed their utmost trust in us. It is our duty to heal with expertise and protect with compassion.”

At Delta Hospital, Huang puts this belief into daily practice. “Delta Hospital is a place of warmth. Doctors take responsibility, and patients show understanding,” he says.

Thirty years ago, a patient underwent surgery with Huang at Fuwai Hospital. Three decades later, that same patient sought him out again, this time at Delta Hospital. Huang is deeply moved when recalling this. “Even now, I sometimes receive local specialties from the hometowns of patients I treated over twenty years ago.”

To better connect with his patients, Huang believes a doctor needs a broad knowledge base. “Beyond my medical expertise, I read widely to understand my patients as whole people. The journey of medicine is walked hand-in-hand with human compassion. When you build a good relationship, miracles can happen.”

In his view, the future of Shanghai Delta Hospital lies in these countless, subtle currents of warmth between doctor and patient. A shared glance of sincerity, the warmth of a reassuring hand, a simple yet heartfelt “thank you”—these moments transcend sterile procedures, weaving a resilient web of compassion. This web forms the bedrock of Delta Hospital’s growth and guides Huang Lianjun’s team to scale even greater heights.

ShanghaiDoctor: We know that Delta Hospital has a strong reputation for treating aortic dissection. Can you recall when you first heard of this disease?

Dr.Huang Lianjun:

Back in my university days in the 1980s, I had never heard of it. It wasn’t until I started working at Fuwai Hospital that I encountered it. I searched the library and finally found it mentioned in a large encyclopedia, which described it as a “rare disease.” In those days, diagnosing it was extremely difficult, and even when a diagnosis was made, there were no effective treatments. With advancements in society and technology, we can now diagnose this condition in a timely manner for patients of all ages, from 20 to 90.

ShanghaiDoctor: In your opinion, what are Delta Hospital’s key advantages? What makes its approach to patient care unique?

Dr.Huang Lianjun:

Delta Hospital is a foreign-invested hospital, but its advantage lies in a service model that is not driven by profit and is highly personalized. Generally speaking, our treatment costs are not excessive. We are very confident in our technical capabilities, especially in the fields of cardiovascular and great vessel intervention.

ShanghaiDoctor: You mentioned government support. How has this support contributed to Delta Hospital’s development?

Dr.Huang Lianjun:

Government support is evident in policy and resources. For example, favorable medical insurance policies allow us to charge at the Tier 3 settlement rate. We also benefit from policies for Shanghai’s high-level medical institutions, can offer direct billing for patients with commercial insurance, and are permitted to use certain medications and devices through self-pay channels. The government also encourages our philanthropic activities, which has earned us greater social trust.

ShanghaiDoctor: You mentioned the risks and responsibilities in cardiovascular disease. What is your philosophy on surgical risk management?

Dr.Huang Lianjun:

In cardiovascular surgery, risk control is paramount. My goal is to ensure every procedure I perform meets the highest possible standards. At the same time, we prioritize clear communication with our patients, helping them understand both the necessity of a procedure and its potential risks.

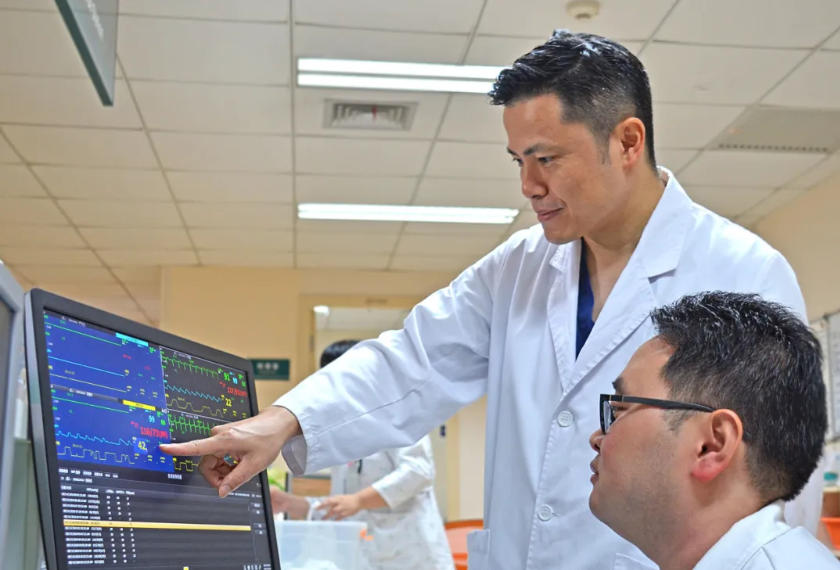

ShanghaiDoctor: What initiatives has Delta Hospital taken in applying Artificial Intelligence?

Dr.Huang Lianjun:

The potential for AI in cardiovascular imaging is vast. We have already integrated AI technologies for tasks like detecting pulmonary nodules and diagnosing heart diseases. While AI may handle more repetitive tasks, we believe it can help us conduct more detailed analyses and improve efficiency. However, I must stress that AI is not currently capable of replacing doctors. From a clinical standpoint, it is nowhere near ready. AI should assist doctors, enabling them to focus on their core expertise. The human connection and empathy between a doctor and patient is something that must always be preserved.

ShanghaiDoctor: Finally, how do you view work-life balance?

Dr.Huang Lianjun:

Given the high-stakes nature of surgery, it’s crucial to find hobbies to unwind and decompress. Personally, I enjoy reading, listening to music, and surfing the internet. These help me regulate my mood and maintain a healthy balance. We encourage our staff to have fulfilling personal lives and strong social networks as well.

Editor: Chen Qing (email:chenqing@ShanghaiDoctor.cn)

If you'd like to contact to Dr. Huang or need help, be free to contact us.

Dr. Lei Tao | Integrating Chinese and Western Medicine, Different Paths to the Same Goal

Dr. Wang Chuanqing | Building a ‘Shield’ for Children: A Guardian Against Pathogens

Dr. Zhou Tingyin | Opening the Door to a World of Microorganism

Dr. Liang Wei | Dedicated to Vascular Health, Safeguarding the Body’s Lifelines

Dr. Zou Shien | A Physician’s Mission in Gynecological World

Dr. Bao Shihua | Where Dreams Begin from Reproductive Immunology

Dr. Yang Zhigang | The Art of the Healer: Between the Brush and the Brain

Dr. Cai Junfeng | Guarding Bone and Joint Health, Improving Quality of Life

Dr. Lei Tao | Integrating Chinese and Western Medicine, Different Paths to the Same Goal

Dr. Wang Chuanqing | Building a ‘Shield’ for Children: A Guardian Against Pathogens

Dr. Zhou Tingyin | Opening the Door to a World of Microorganism

Dr. Liang Wei | Dedicated to Vascular Health, Safeguarding the Body’s Lifelines

Dr. Zou Shien | A Physician’s Mission in Gynecological World

Dr. Cui Song | Healing the Heart, in Every Sense

Dr. Bao Shihua | Where Dreams Begin from Reproductive Immunology

Dr. Yang Zhigang | The Art of the Healer: Between the Brush and the Brain

Dr. Zhou Qianjun | Sculpting Life in the Chest

Dr. Cai Junfeng | Guarding Bone and Joint Health, Improving Quality of Life