Update time:2025-12-07Visits:3788

Dr. Jiang Hong

Dr. Jiang Hong is a Chief Physician in the Department of Neurosurgery at Ruijin Hospital, affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. He graduated from Shanghai Second Medical University (now Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine) in 2002 and has been practicing at Ruijin Hospital’s Neurosurgery Department ever since. From 2005 to 2006, he pursued advanced training at Hospital Louis Pradel in France. With over two decades of experience in neurovascular intervention, Dr. Jiang has established himself as a leading expert in the field.

He holds memberships in several prestigious professional organizations, including the Shanghai Stroke Association of the Shanghai Medical Association, the Stroke Branch of the Chinese Medical Doctor Association, and the Basic and Translational Neurosurgery Group of the Shanghai Medical Association. Dr. Jiang has authored numerous papers on cerebrovascular interventional treatments and has made significant contributions to brain science research, with over 30 SCI-indexed publications to his name. One of his works was featured as a cover article in an internationally renowned journal.

His clinical expertise focuses on the prevention and treatment of stroke, as well as interventional therapies for cerebral and spinal vascular diseases. He specializes in stent placement and embolization for intracranial aneurysms, cerebral arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), and intracranial/extracranial arterial stenosis, including carotid artery stenosis.

Introduction

Since childhood, he has grown alongside every tree, brick, and tile of Ruijin Hospital, witnessing its continuous growth and evolution. Nurtured by this century-old institution steeped in compassion and excellence, he has deeply rooted himself in its rich history while drawing strength from the advancements of the present, quietly rising to shape his own journey.

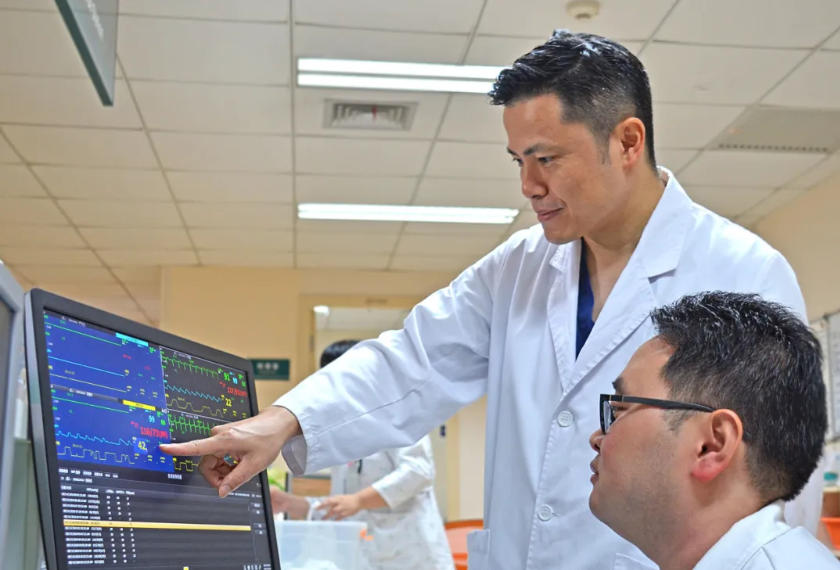

Guided by wisdom and skilled hands, he navigates the body’s most intricate and profound vascular labyrinths—a realm where life and death converge, and disease lingers in shadow. With an almost reverent focus, he and his colleagues work in these microscopic worlds, often on the razor’s edge between survival and loss, rekindling faint sparks of life for countless patients in critical condition.

Day after day, his team ventures into the vast, intricate networks of blood vessels—a path with no end, yet filled with purpose and hope.

Medical Seed in Heart

Dr. Jiang Hong describes the medical seeds that took root in him at Ruijin with quiet reflection: “I was born here and spent much of my childhood around the hospital. Ruijin used to have many buildings from the 1930s—old structures full of character. Then, gradually, new towers rose… I watched it change, and I grew up along with it. It’s a rather special feeling.”

Shanghai’s Ruijin Hospital—a century-old institution steeped in medical excellence—was not just part of Jiang Hong’s childhood; it was his playground, his classroom, and the very cradle of his lifelong dedication to medicine. His father was a radiologist at Ruijin, and his mother worked in the radiology department at Zhongshan Hospital. While other children played outdoors, Jiang’s world was intertwined with the hushed, mysterious corridors of the hospital—the hurried footsteps, the faint glow of X-ray films on light boxes, the sense of purpose that filled the air.

“Back then, the hospital felt like a second home,” he recalls, a touch of warmth in his voice. “My parents were often busy, so after school I’d wander the halls. I watched my father develop films in the darkroom and my mother analyze images under the viewing lamp. Those black-and-white images held a kind of silent fascination.”

Though no one in his extended family had practiced medicine, the white coats of his parents planted an early seed in his heart. By the 1990s, as finance and computer science captivated an entire generation, Jiang Hong found himself at a crossroads. “To be honest,” he reflects, “medicine felt familiar—almost like an old friend. I understood its temperament and its weight.” That sense of connection, along with his father’s ties to Ruijin, led him to Shanghai Second Medical University (now Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine).

To outsiders, Jiang’s path might have seemed preordained: born into a medical family, graduated from a prestigious school, joined a top-tier hospital, learned from masters, and rose in a cutting-edge specialty. But only he knows how much resilience it truly required. “I attended Shanghai Nanyang Model High School and did well academically. I wasn’t the very top in science, and finance never appealed to me. When I entered medical school, I ranked third in my cohort. But medical training was intense—through my master’s and doctoral studies, it never let up. I’ve always believed perseverance matters more than brilliance. If you choose to climb, you can’t stop halfway.”

July 10, 2000, marked a defining moment: Jiang Hong officially began his career in the Department of Neurosurgery at Ruijin Hospital. That day, he put on his white coat not as a visitor or a student, but as a doctor—stepping into the revered halls that had shaped his childhood.

“When I started, neurointervention was still an emerging field in China. It had only begun here around 1996–1997. Ruijin launched related treatments in 1998. By the time I entered in 2000, the future of the discipline was still uncertain,” he recalls. Neurointervention in China at that time was uncharted territory—a blue ocean of both risk and possibility.

When Jiang rotated into the neurointerventional team, he was drawn to this hybrid specialty blending neurosurgery, radiology, and endovascular techniques. Unlike dramatic open-skull surgeries, neurointervention resembled “micro-sculpting” within the body’s most delicate vascular networks. “Its biggest advantage is that it’s minimally invasive and relatively accessible,” he explains. “That made it easier for young doctors to learn, experiment, and innovate.”

The minimally invasive nature meant less suffering for patients and faster recovery—but it also demanded extremely refined skill and precision from physicians. Jiang recognized early the immense potential of solving complex problems with subtlety and grace.

From 2005 to 2006, he went to Lyon, France for advanced training—an experience that profoundly expanded his perspective. “Neurointervention started much earlier in France. By the time I arrived, French surgeons were already highly skilled. We were able to learn from the challenges they had already overcome. That’s the advantage of starting later—you can avoid the pitfalls of early exploration.”

In operating rooms in Lyon, he observed advanced technology, standardized protocols, and an almost obsessive attention to detail. More importantly, he saw a future for neurointervention in China: though it started late, the combination of “late-mover advantage” and vast clinical experience could lead to rapid, transformative progress.

“Now China is developing extremely fast,” Jiang says with pride. “Our field has advanced to the forefront globally.” Chinese neurointervention has evolved from imitation and learning to innovation and leadership. In recent years, unique clinical challenges faced by Chinese physicians have spurred original techniques and materials. “Some methods were pioneered here in China first,” he emphasizes. “These innovations will increasingly contribute to global medicine.”

The Aneurysm “Revolution”—A Leap from Open Surgery to Intervention

In the history of neurointervention, the treatment of intracranial aneurysms has been nothing short of a revolution—one defined by a fundamental shift in approach: from opening the skull and placing clips under direct vision to navigating the intricate pathways of blood vessels and addressing the problem from within using micro-scale tools.

“When open surgery was the only option, mortality rates for aneurysms in certain locations could reach 5–10%,” explains Dr. Jiang Hong. “But as neurointervention matured, those rates began to drop steadily. Today, we’ve managed to bring them down to around 1%.”

He recalls the high-stakes reality of earlier years with clarity: “I’ve reviewed the literature—back in 1996, the rate of major complications from basilar apex aneurysms was between 10% and 25%. That meant one out of every four or five patients risked severe disability or even death.” These daunting odds once made both doctors and patients hesitate. Performing surgery near the brainstem was like dancing on the edge of a cliff.

The advancement of neurointervention has rewritten that grim reality. “Nowadays, open surgery for basilar apex aneurysms has largely been phased out,” says Dr. Jiang, his tone conveying a sense of historical closure.

Yet technological progress never stands still. While traditional coil embolization significantly reduced risks, it still faced a stubborn 2–3% rate of mortality and disability. “No matter how skilled we are, we couldn’t completely eliminate those risks,” Dr. Jiang admits.

Over the past decade, a new generation of devices—most notably flow diverters—has brought another leap forward. “With flow diverters, especially for complex aneurysms, we’ve been able to reduce mortality and disability to around 1%.” Unlike coils, which fill the aneurysm, flow diverters act like a finely-woven net placed across the aneurysm’s neck. They alter hemodynamics, promoting thrombosis and endothelial repair—working in harmony with the vessel’s natural biology.

“Blood vessels are living organs, not bicycle tires,” Dr. Jiang illustrates. “Fixing a tire is about plugging a hole physically. But when a vessel is diseased, if we can reduce stress and provide the right support, it often has the power to heal itself. The question is: to what extent can it truly recover?”

This reverence for the body’s innate healing capacity drives Dr. Jiang and his team to continually pursue treatments that are less invasive, more physiological, and more effective. Every innovation represents a deeper commitment to preserving the dignity of life.

It also demands patience and relentless exploration. “Boundless Compassion, Pursuit of Excellence”—the motto of Ruijin Hospital—captures not just an institutional ethos, but a personal conviction that has shaped Dr. Jiang’s journey.

“What defines Ruijin is its comprehensiveness,” he emphasizes. Neurointervention does not work in isolation—it requires close collaboration across neurology, neurosurgery, radiology, critical care, anesthesiology, cardiology, endocrinology, and more. At Ruijin, such interdisciplinary cooperation is ingrained in the culture.

“Many of the patients we see have complex, multi-system conditions,” Dr. Jiang notes. “They might present with severe heart disease, renal failure, endocrine crises, or even be pregnant. Cases like these can be challenging for highly specialized hospitals, but at Ruijin, we have robust multi-disciplinary support.”

He highlights the essential role of the ICU, particularly after emergency interventions. Ruijin’s strong critical care infrastructure provides a safety net that allows physicians to take on higher-risk cases with greater confidence.

This systematic, team-based approach has also benefited other hospitals. Dr. Jiang recalls one especially complex case: a patient in his fifties with end-stage renal disease, long-segment severe stenosis of the internal carotid artery, and a giant aneurysm. The man had suffered repeated strokes and developed ocular paralysis; his condition was critical. After being turned down by multiple hospitals due to the extreme risks, he returned to a local hospital in Nankang County, Jiangxi Province, which then reached out to Dr. Jiang’s team.

“The risks were tremendous,” Dr. Jiang recalls. “His renal failure meant abnormal coagulation and fragile vessels—high risk of bleeding during and after the procedure. The giant aneurysm was a ticking time bomb, and treating the stenosis could have dislodged clots. Any misstep would have been catastrophic.”

Yet the patient’s determination, his family’s trust, and the local team’s eagerness to learn moved Dr. Jiang. He flew to Nankang and, working closely with local doctors under relatively basic conditions, successfully performed carotid stenting and flow diverter implantation.

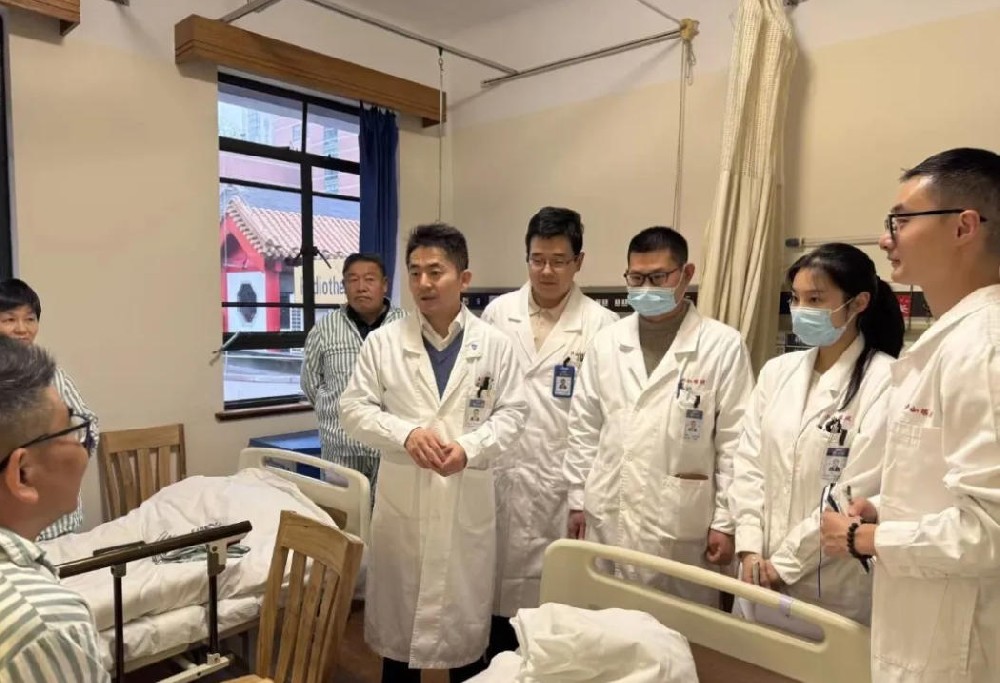

Afterward, the patient received dialysis and careful medication management locally and eventually recovered. “The surgery alone wasn’t enough,” reflects Dr. Jiang. “What made the difference was the postoperative care and the courage of the local team. They took on the challenge and are now equipped to handle similar cases. That’s how we help regional hospitals grow.”

This case exemplifies Ruijin’s commitment to “bringing expertise to the grassroots.” Through alliances, surgical mentoring, and training programs, Dr. Jiang and his team have extended Ruijin’s knowledge and technology to hospitals across the region and beyond.

“We work with over a dozen medical alliances,” he shares. “When there’s a need, we go. Real change happens when local doctors gain the skills and confidence to use these techniques themselves.”

It brings him satisfaction to see hospitals that once received support from Ruijin now thriving and even assisting other facilities in their areas. This spirit of “teaching how to fish” is how Dr. Jiang embodies “boundless compassion”—a legacy of care that continues to spread.

The Boundary of Ethics: Navigating the Unknown with Reverence

Medical progress is inextricably linked to the exploration of the unknown—and in that process, it continually tests the boundaries of ethics. In neurointervention and beyond, Dr. Jiang Hong maintains a stance of clear-eyed caution. This attitude becomes especially critical when confronting the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s.

Several years ago, there was growing interest—even enthusiasm—around exploring cranial lymphatic drainage surgery as a potential treatment for Alzheimer’s. Some hospitals were preparing to launch clinical applications. At the time, Dr. Jiang was also conducting related research.

“Scientifically, it wasn’t necessarily wrong to investigate,” he acknowledges. “But I believed we needed to understand the mechanism first before pursuing treatment.” He notes that in his own studies, certain brain injury patients did show impaired lymphatic function. Yet, he adds, “the relationship between lymphatic impairment and cognition—and how to improve it—remained unknown.”

This honesty about the “unknown” is, to him, the very foundation of responsible medical inquiry. When asked whether such surgery could effectively treat Alzheimer’s, Dr. Jiang is unequivocal: “The scientific answer is—we don’t know.” He understands all too well that proceeding with human surgeries without clear mechanisms or proven efficacy would expose patients to unpredictable risks.

His caution is rooted in a deep understanding of medical ethics and lessons from history. Dr. Jiang brings up a sobering example: the lobotomy.

In the 1930s, the United States widely performed lobotomies on psychiatric patients. The procedure did show effects in some cases—so much so that a physician involved even received a Nobel Prize. Yet within just five years, it was banned.

Why? Dr. Jiang points to this episode as a catalyst for the birth of modern medical ethics. “There are ‘valuable data’ obtained at the cost of human suffering—data on survival under extreme conditions, for example—that might be published in top medical journals. But the manner in which they were acquired would horrify any ordinary person.”

It was these painful chapters in medical history that helped shape core ethical principles today. “The earliest ethical protocols emphasized that the benefits to the many cannot come at excessive cost to the individual. We cannot sacrifice an individual’s rights and dignity in the name of so-called ‘collective benefit’.”

He further reflects that even into the 1950s and 60s, the rights of psychiatric patients or those with intellectual disabilities were often overlooked. These historical reckonings have gradually led the medical community to recognize that every life, regardless of condition, possesses inherent dignity and inviolable rights.

“With any treatment—especially exploratory ones—we must ask ourselves: Have we fully respected the patient’s right to informed consent? Have we minimized risks to the greatest extent possible? Is there sufficient scientific evidence to support our approach?”

Dr. Jiang’s reflections go beyond technical skill—they touch the very heart of medical practice: humanity and care. On the frontlines of neurointervention, he stands as a guardian who measures progress with an ethical compass and approaches the unknown with reverence—carefully defining that critical line between exploration and the protection of life.

The Weight of Trust—A Leap of Faith at the Edge of Life and Death

In neurosurgery, particularly in neurointervention, doctors often face decisions where life hangs in the balance. While technical skill is essential, what sustains a physician working under extreme pressure and high risk is not just expertise—it’s something intangible yet immensely powerful: the trust of their patients.

Dr. Jiang Hong recalls one unforgettable case. A patient was admitted after a stroke, and imaging revealed severe stenosis in one of the middle cerebral arteries. But there was a further complication: an unruptured aneurysm was found just proximal to the narrowed segment.

The treatment dilemma was profound: addressing the stenosis risked triggering aneurysm rupture during the procedure, while treating the aneurysm could compromise blood flow restoration in the already narrowed vessel.

As the medical team weighed their options, the patient’s condition suddenly deteriorated that very night. Emergency intervention became unavoidable.

“The risks were enormous,” Dr. Jiang recalls. “Performing an emergency revascularization with an aneurysm present carried an estimated mortality rate of 10–20%—ten to twenty times higher than our usual 1–2%.”

There was no time to hesitate. Dr. Jiang and his team explained the grave risks and possible outcomes with complete honesty to the family. After a long, heavy silence, the family looked up, their eyes filled with fear and hope—but above all, with a profound, almost solemn trust. “We believe in you,” they said. “Please do what you must.”

“In that moment, what you feel isn’t just responsibility—it’s a weighty entrustment,” Dr. Jiang says, his voice softening. “The few seconds the pen hovers over the consent form… the weight of that trust is greater than any surgical instrument.”

The team proceeded under tremendous pressure and successfully reopened the blocked vessel. However, to safely use the stent to cover the neck of the aneurysm, making subsequent treatment far more complex and risky.

Confronted with this new challenge, the team did not retreat. After reassessment and reaffirmed trust from the family, they skillfully navigated around the stent and neutralized the “ticking time bomb.” The patient ultimately recovered completely.

“He came back for a follow-up just the other day,” Dr. Jiang shares with visible warmth. “Seeing him doing so well, remembering those words—‘we believe in you’—it really moves me.”

Trust is the most precious bond between doctor and patient. It gives physicians the courage to operate at the edge of possibility, and patients the strength to place their lives in someone else’s hands. For Dr. Jiang, this trust has been like a warm light in the operating room—illuminating countless critical nights and supporting him as he pushes the boundaries of medicine to protect fragile, invaluable lives.

“Every life is unique. Every family places their entire hope in us. Without the trust of patients and their families, and without emotional commitment, many high-risk surgeries simply wouldn’t be possible,” he reflects.

At Ruijin Hospital, in the consultation rooms and operating theaters of the neurointervention department, Dr. Jiang is not only a technical leader but also a representative of a new generation of physicians. The passing of the torch in medicine requires dedication across generations. Faced with growing patient needs and intense workloads, he eagerly looks forward to the rapid growth of young doctors who can carry neurointervention to new heights.

“Our emergency caseload is quite heavy,” Dr. Jiang notes, expressing both fatigue and hope. “Doctors over forty, like myself, are handling seven, eight, even nine emergency shifts a week. It’s physically demanding.” He hopes young physicians can mature quickly—to share the burden and help more patients.

This expectation stems not only from a sense of duty to the field but also from his confidence in the potential of the next generation.

What, then, are the core qualities of an outstanding neurointerventionist?

“First and foremost: compassion and resilience,” he states without hesitation. In his view, while intelligence is important in navigating medicine’s vast and unpredictable landscape, what truly allows a doctor to go far and climb high is a “heart of compassion” and “unwavering perseverance.”

“Over the years, I’ve come to believe that medicine requires a blend of science and humanity—but what matters most isn’t knowledge or technical talent.” Those who endure and thrive, he says, are those who remain resilient in the face of relentless challenges.

This resilience is the spiritual legacy he most wants to pass on.

Close behind comes “humanistic care.” A doctor, he believes, must possess empathy—the ability to understand what patients and families are going through. Neurosurgeons regularly confront life and death, but they must never become desensitized. A good doctor doesn’t just “treat the disease”—they must also “see the person.” Understanding the pain, anxiety, and helplessness that illness brings allows physicians to build bridges through empathy and ease fears with warmth.

This human touch is the foundation of trust between doctor and patient—and an invisible yet powerful force that elevates healing.

Dr. Jiang believes that these sparks of compassion and resilience, once kindled in young doctors, will gather into a light that illuminates the future of neurointervention at Ruijin—a future shining bright with hope and excellence.

ShanghaiDoctor: We’ve noticed that you’ve been focusing recently on advancing the application of flow diverter (FD) technology. Could you elaborate on your current goals in this area?

Dr. Jiang Hong: Indeed, my immediate goal remains to further mature the clinical use of FD technology. On one hand, it’s about accumulating more experience; on the other—and most importantly—it’s about expanding access for more patients. To be frank, this is currently my preferred surgical approach. Its greatest advantage lies in simplifying procedural risks and significantly reducing patient trauma. It represents a major step toward minimally invasive and more physiological treatments in neurointervention, offering renewed hope to patients with complex aneurysms at a lower cost. Refining this technique, applying it more broadly, and benefiting more patients—that’s my most urgent and concrete objective at this stage.

ShanghaiDoctor: That sounds highly pragmatic. When it comes to your longer-term personal development, what vision do you hold? Do you have any larger ambitions or plan?

Dr. Jiang Hong: Regarding personal growth, my perspective is actually quite simple: I believe in taking solid, deliberate steps forward. Actions speak louder than grand plans. It might sound modest, but it’s a conviction shaped through decades of medical practice. Rather than investing energy in distant or abstract visions, I focus on the present—each surgery, each patient, every opportunity to learn and reflect. Real progress is built through concrete action, one step at a time. This is not only what I expect of myself, but also what I sincerely hope to impart to younger doctors.

ShanghaiDoctor: You’ve repeatedly emphasized being “grounded and steadfast.” This attitude seems deeply connected to your strong ties with Ruijin Hospital. From becoming familiar as a child with its atmosphere, sounds, and hurried footsteps, to now serving as a neurointervention specialist protecting lives—what does this shared growth, this “growing up together with the hospital,” mean to you?

Dr. Jiang Hong: Yes, my bond with Ruijin runs deep. I’ve watched it gradually become what it is today, and it has witnessed my own journey from inexperience to maturity. This connection fills me with both a sense of belonging and responsibility. I am committed to contributing my expertise to help maintain Ruijin’s leading position in neurointervention, so that this hospital I deeply care for can continue advancing steadily and purposefully in safeguarding lives. This “growing up together” makes me feel that my personal development is inseparable from the hospital’s progress.

ShanghaiDoctor: Finally, how do you see the future of artificial intelligence (AI) in neurointervention?

Dr. Jiang Hong: At its core, AI relies on algorithms—including the understanding and application of underlying computational models. In neurointervention, I anticipate significant leaps within the next five to ten years. Promising applications include accurate prediction of postoperative outcomes and optimized design of personalized surgical plans. However, the real breakthrough may come in areas beyond our current imagination. Blood vessels are living organs capable of self-repair after injury. We especially want to predict the extent of repair in advance, rather than waiting one or two years after surgery for follow-up. In the future, we hope to integrate AI with imaging, fluid dynamics, and other multimodal approaches to truly understand disease mechanisms, quantify treatment indications, and clarify what requires intervention and what can be monitored. This would mark a shift from “reactive intervention” to “proactive guidance”—a direction we are striving toward. Of course, AI is not a magic solution; it must be built on a massive foundation of clinical data and rigorous groundwork.

Hospital: Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine

Editor: Chen Qing, ShanghaiDoctor.cn

If you'd like to contact to Dr. Jiang, please be free to email us at Chenqing@ShanghaiDoctor.cn.

Dr. Lei Tao | Integrating Chinese and Western Medicine, Different Paths to the Same Goal

Dr. Wang Chuanqing | Building a ‘Shield’ for Children: A Guardian Against Pathogens

Dr. Zhou Tingyin | Opening the Door to a World of Microorganism

Dr. Liang Wei | Dedicated to Vascular Health, Safeguarding the Body’s Lifelines

Dr. Zou Shien | A Physician’s Mission in Gynecological World

Dr. Bao Shihua | Where Dreams Begin from Reproductive Immunology

Dr. Yang Zhigang | The Art of the Healer: Between the Brush and the Brain

Dr. Cai Junfeng | Guarding Bone and Joint Health, Improving Quality of Life

Dr. Lei Tao | Integrating Chinese and Western Medicine, Different Paths to the Same Goal

Dr. Wang Chuanqing | Building a ‘Shield’ for Children: A Guardian Against Pathogens

Dr. Zhou Tingyin | Opening the Door to a World of Microorganism

Dr. Liang Wei | Dedicated to Vascular Health, Safeguarding the Body’s Lifelines

Dr. Zou Shien | A Physician’s Mission in Gynecological World

Dr. Cui Song | Healing the Heart, in Every Sense

Dr. Bao Shihua | Where Dreams Begin from Reproductive Immunology

Dr. Yang Zhigang | The Art of the Healer: Between the Brush and the Brain

Dr. Zhou Qianjun | Sculpting Life in the Chest

Dr. Cai Junfeng | Guarding Bone and Joint Health, Improving Quality of Life