Update time:2026-02-03Visits:777

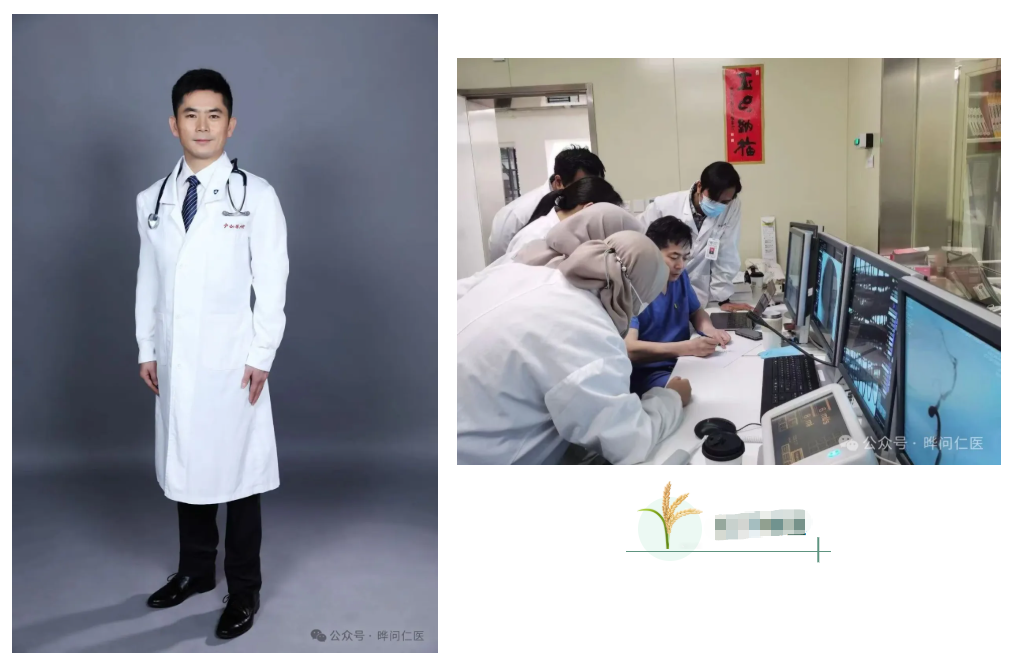

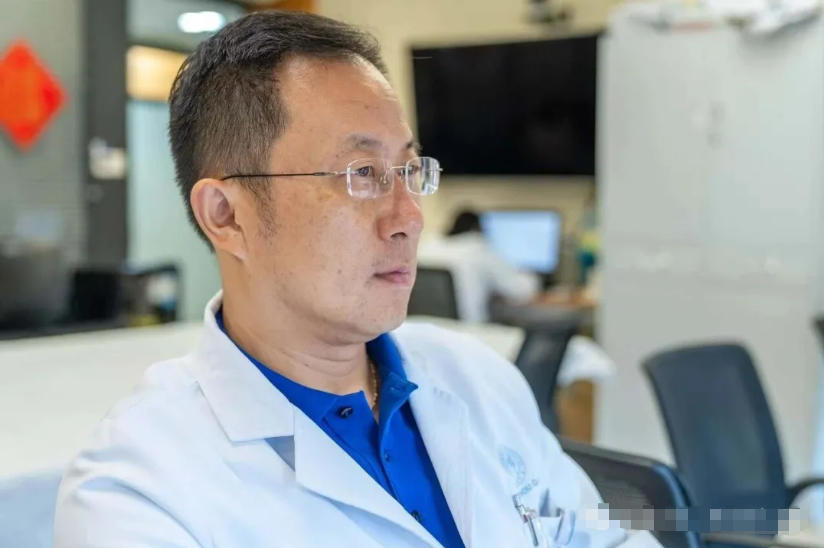

Dr. Yang Zhigang

MD, PhD, Associate Chief Physician, Master’s Supervisor.

Dr. Yang currently serves as the Secretary for the Neurointervention Division of the National Clinical Research Center for Radiological and Medical Imaging, and the Deputy Director of the Comprehensive Center for Neurovascular Diseases at Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University. He is also the Director of the Sub-specialty for Minimally Invasive Treatment of Cerebral and Spinal Vascular Diseases at the Department of Neurosurgery, Zhongshan Hospital.

He has participated in numerous national-level research projects, leads four research projects funded by the Shanghai Science and Technology Commission, and has published over 30 papers in leading journals, including Nature Communications. His accolades include a First Prize in Medical Achievement Awards from both the Ministry of Education and the Shanghai Municipal Government. He holds 3 national invention patents and 9 utility model patents, has contributed to four specialized monographs, and serves as a reviewer for World Neurosurgery and the Chinese Journal of Clinical Medicine, as well as a Youth Editorial Board Member for Metaverse Medicine.

First Perspective

He is a young man who emerged from the wheat fields of the Northwest; a virtuoso "swordsman" dancing amidst the black and white shadows of medical imaging; a healer seeking equilibrium between technology and philosophy.

With over twenty years of medical practice, he has defined the true meaning of "refinement"—a profound reverence for life, an unshakable confidence in his craft, and a deep, abiding compassion for the world.

The calligraphy on his desk begins with rustic simplicity, moves through exquisite precision, and ends in translucent clarity. In the operating theater, his micro-guidewire is the brush, and the blood vessel is the delicate rice paper. Only through the "honing of daily practice"—that relentless repetition—can one cultivate the steadiness and precision required to sketch a sense of peace and fluid grace amidst the stark black and white contrasts of life and death.

In the microscopic universe of the cerebrovascular system, he continues to write sacred chapters of life guardianship with a sense of calm detachment that is "just right."

1. Northwest Reminiscences: A Craftsman’s Original Aspiration

On the heavy, vast land of the Northwest, summers in Gansu always possess a scorching, tactile intensity. In his youth, Yang Zhigang stood countless times amidst the rolling wheat waves, helping his elders harvest under the blazing sun, sweat pouring like rain. These were his earliest memories of "survival" and "toil," and they became the primal force driving him to break free and seek another possibility for his life.

At that time, Yang’s ideal was concrete: to secure a job where he wouldn't have to labor with his "face to the loess and back to the sky" during the hottest days of the year—to be able to stand on his own two feet.

Recalling those years, Yang said: "I come from a rural village in the Northwest. My childhood dream was simple: have a job so I wouldn't have to work in the fields—cutting wheat, turning the soil—under the scorching sun. The moment I was admitted to military medical school, I realized I wouldn't have to spend my parents' hard-earned money anymore; I could support myself. That sense of joy is unforgettable."

This desire for independence and survival guided him through the gates of the First Military Medical University. His dedication to medicine was influenced by his aunt, a pediatrician who saved family members, but it was rooted even deeper in a simple, traditional value: "In times of famine, the skilled craftsman never starves."

He has always viewed medicine as a solid, grounded "craft" intimately connected to the daily lives of ordinary people—one that solves urgent, practical problems while accumulating virtue.

The ancient medical classic The A-B Classic of Acupuncture and Moxibustion (Zhenjiu Jiayi Jing) states: "If one is not skilled in medicine... when one's ruler or father is critically ill, or innocent children are suffering, one has no means to save them." These words by Huangfu Mi deeply resonated with Yang. He understood that without medical knowledge, one is helpless when a loved one falls ill. He aspired to be the one who could extend a helping hand. Furthermore, his 18-year military career forged a dual identity—"soldier and doctor"—instilling a backbone of resilience and responsibility in his very bones.

When he first started, he aspired to orthopedics. In his imagination, the orthopedic surgeon was a "hero of trauma" performing grand, sweeping maneuvers—patients came in on stretchers and walked out on their own feet.

However, during his internship, his keen nature and pursuit of perfection led him to feel, somewhat obsessively, that the logic of orthopedics sometimes resembled "carpentry." It seemed to lack the exquisite nuance and mystery he craved.

Thus, he turned to the "crown jewel" of the medical world: Neurosurgery.

The brain, as the vessel of human higher intelligence, is filled with the unknown and infinite possibility. The challenge of exploring the mysteries of cognition within a microscopic space ignited his professional passion.

"I love challenge. The fascination of neurosurgery lies in the vast unknown within the brain. What makes us human is primarily our higher intelligence. I felt this was a field worth dedicating a lifetime to explore."

During his decade at the military medical university—from his bachelor’s and master’s to his doctoral studies—Yang’s every step was solid. Two mentors left a lifelong mark on his path. One was Professor Li Tielin, a titan of neurointervention, who introduced Yang to the magic of the procedure: curing a brain ailment through a single needle puncture in the groin. The other was his doctoral supervisor, Professor Liu Jianmin, a leading figure who brought China’s clinical research in cerebrovascular disease to the global forefront. Professor Liu’s "idealistic" passion and his "high adversity quotient"—the ability to see the positive in any pressure—became Yang’s lighthouse. Crucially, the "devil’s training" (rigorous boot camp) at the Cerebrovascular Disease Research Institute of the PLA Changhai Hospital laid the most solid and profound foundation for Yang’s technical skills.

From the wheat fields of the rural Northwest to the sacred halls of medicine, Yang Zhigang has embarked on a journey of redemption and guardianship, armed with a purity that borders on obsession.

2. A Universe at the Fingertips: The Dance of the Millimeter

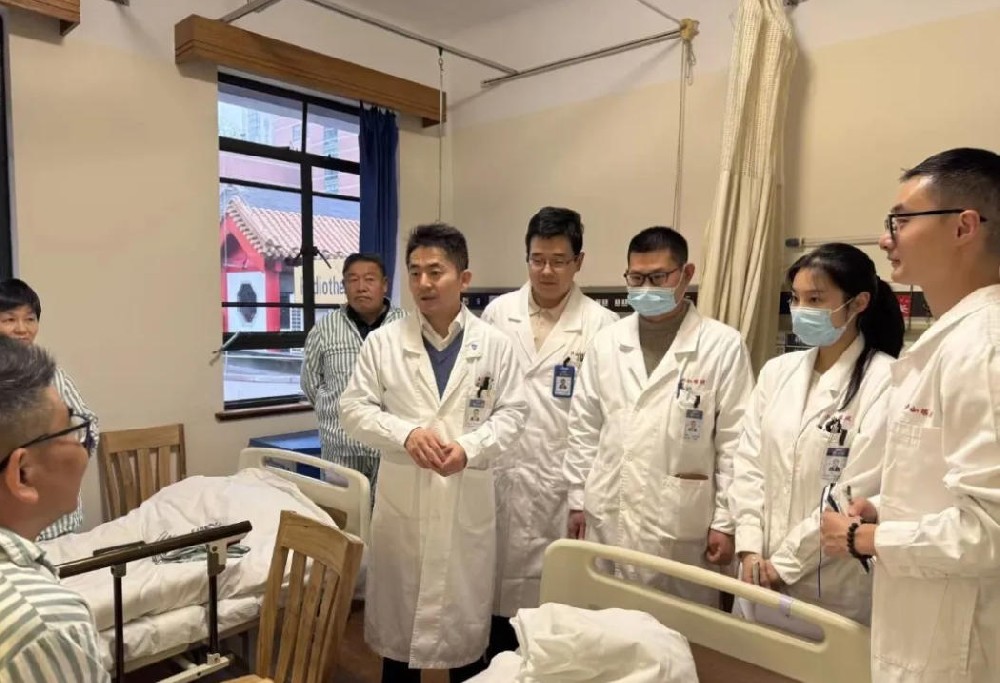

To understand Dr. Yang Zhigang’s journey in neurosurgery, one must look at the tenure he built at Zhongshan Hospital.

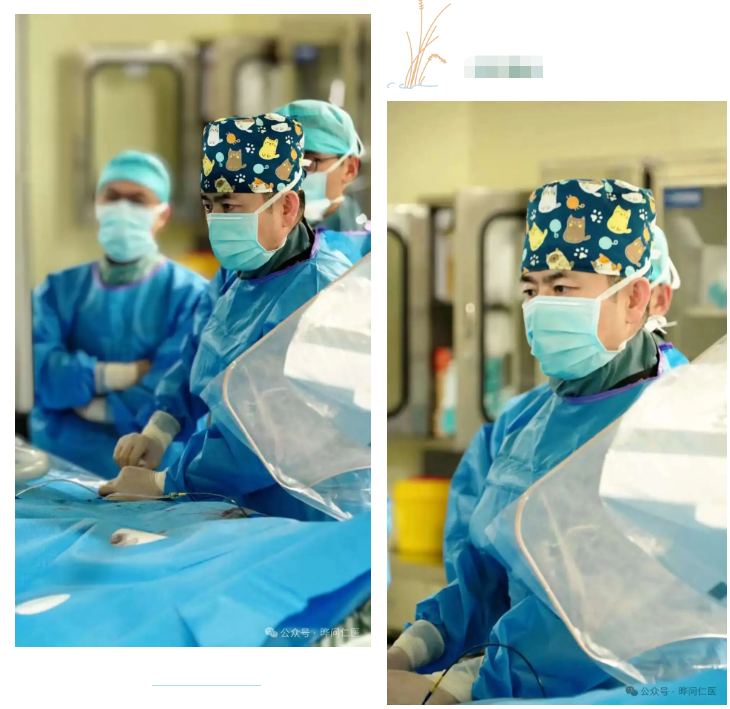

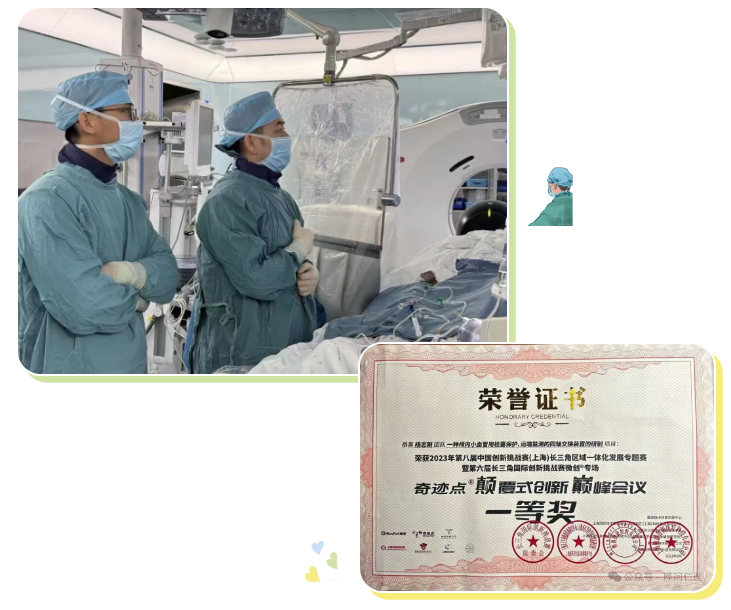

Neurointerventional surgery is an “extreme challenge” conducted within the blood vessels. The physician navigates a vascular pathway, manipulating a guide wire as thin as a hair to traverse cerebral vessels that are complex as a maze and fragile as thin ice. The objective is to defuse “ticking time bombs”—such as aneurysms—before they explode.

When Yang first arrived at Zhongshan Hospital, the foundation for cerebrovascular disease treatment was still nascent, with a surgical volume of just over 100 cases a year. However, with the support of hospital leadership and the collective effort of his team, Zhongshan Hospital established the Comprehensive Center for Neurovascular Diseases. It is now a key component of the National Clinical Research Center for Radiological and Medical Imaging. Both the volume and quality of surgeries have seen explosive growth in a short time, surpassing 2,300 procedures last year alone. This leap in numbers reflects Yang Zhigang and his team’s relentless pursuit of efficiency and quality.

For every surgery, Yang Zhigang insists on the standard of “refinement.” He champions the philosophy of Professor Ling Feng, a pioneer of neurointervention in China: “Perform refined surgeries; be a person of distinction.”

Yang possesses a unique insight into what “refinement” means. “Our goal is the pursuit of zero complications,” he says. “While achieving absolute zero in practice is impossible, it must remain our ideal state. Refinement is not about nitpicking; rather, it is about striving for perfection while, in that specific moment, choosing the most reasonable solution for the patient—striving to achieve a state that is ‘just right.’”

This philosophy was tested when he performed surgery on his own mother after she suffered a sudden 70ml brain hemorrhage. While many doctors adhere to the convention that “physicians should not treat their own kin,” Yang displayed extraordinary calm and confidence. That his mother continues to live a normal life stands as proof of his precise judgment.

“I knew that in that situation, among all the doctors I could reach, I was the most skilled,” he admits. “I had that confidence, so I could operate with a steady mind. Operating on a loved one is the true test of a doctor’s level. If you hesitate, it means your professional skills are not solid enough. This is not just a psychological factor; it is a matter of confidence in your own craft.”

This confidence is not blind arrogance, but is built upon tens of thousands of operations and thousands of successful cases. Yang is a “Virgo” perfectionist, yet his deep study of traditional culture has grounded him in the Dao of “Balance.”

On the operating table, he never “lingers” unnecessarily, nor does he “show off.” He believes in the Taoist maxim: “Great skill appears effortless.”

He once encountered an extremely complex case. After treating it to a certain extent, he made the decisive call to stop. He realized that continuing to pursue a kind of “visual perfection” would introduce risks far outweighing the benefits. In fact, after the initial surgery helped the patient survive the critical period, new medical materials became available. Through a simple, safe secondary surgery, the patient was easily cured.

“Exerting too much force easily leads to distorted movements,” he often says. For him, the highest realm of surgery is not extreme complexity, but the “just right” kind of precision. This wisdom of the Golden Mean allows him to always find the path most beneficial to the patient on the treacherous battlefield of cerebrovascular treatment.

On the last day of 2025, Yang Zhigang and his team completed five high-difficulty surgeries consecutively. Yet, at 5:00 PM, as the last patient was safely returned to the ward, Yang was able to clock out on time to spend New Year’s Eve with family and friends. This work-life balance was achieved thanks to the team’s thorough discussion the night before, the detailed surgical protocols established, and the seamless coordination of the team—which flowed as fluidly as moving clouds and water.

He smiled, “This was one of my warmest moments in 2025.”

3. Benevolence and Expertise: Guarding the Warmth of Life

In Dr. Yang Zhigang’s consultation room, the atmosphere is always warm.

More than twenty years ago, while serving as an attending physician at Changhai Hospital, Yang performed a complex embolization surgery for a dural arteriovenous fistula on a patient—an older sister. Today, she is nearly 70. Every festive season, she still sends him greeting cards and traditional zongzi (sticky rice dumplings), and whenever she visits Shanghai, she makes sure to see him. In her eyes, Yang Zhigang is no longer just a doctor in a white coat; he is family, the guardian of her life.

Yang believes that the essence of medical service is to meet the health needs of the patient, not to merely apply cold data and rigid templates of evidence-based medicine.

He has treated countless patients with brain aneurysms. Many arrive holding check-up reports, asking in panic: “Doctor, when will this bomb in my brain explode?” Faced with this anxiety about the unknown, Yang never simply throws out cold probability statistics. He analyzes the situation from both medical and psychological dimensions: for a cautious patient who has lost their appetite and sleep over the fear, he leans toward minimally invasive surgery to untie the “knot in their heart”; for a patient who resists surgery, as long as the risk is controllable, he advises regular follow-ups, returning the autonomy of life to the patient.

Yang smiles and says, “Often, the disease itself may not cause massive harm, but the emotion of anxiety can destroy a person’s quality of life. The treatment of many diseases is, in essence, a humanistic and philosophical issue.”

This insight into the human condition has earned Yang friendships that transcend the typical doctor-patient relationship. His phone is filled with “good news” messages from patients. One was the daughter of a patient with a ruptured aneurysm; years later, she sent Yang her wedding candy. Later, when that family welcomed a new member, he received the traditional “joyful eggs.”

He also once saved a young man who had just received his university admission letter but was diagnosed with a cerebrovascular malformation—initially misdiagnosed as a hemorrhage. Thanks to Yang’s accurate judgment and meticulous treatment, the boy recovered smoothly and later married. Poignantly, inspired by Yang’s professional dedication, the boy’s wife eventually chose to study medicine, specializing specifically in cerebrovascular diseases. This relay of spirit is perhaps the highest commendation a doctor can receive.

For the families of patients with acute stroke, Yang displays a different kind of “hardcore” tenderness. When signing informed consent forms before surgery, families often fall into intense ambivalence. At these moments, Yang is never ambiguous; instead, he provides clear directional advice backed by a strong sense of responsibility.

“The more the patient hesitates, the more the doctor must give a clear inclination,” Yang says. “I tell them: ‘If this patient were my family, this is how I would choose.’ This is not just professional confidence; it is moral responsibility. The doctor and the patient are comrades-in-arms, not enemies. Only through cooperation and trust can we work together to defeat the disease.”

In Yang’s view, these warm stories are the source of his resistance to professional burnout and his ability to maintain a high “Adversity Quotient.” No matter how busy the work or how cumbersome the system, as long as he sees the smile of a cured patient, that sense of achievement is something no other profession can replace.

4. Deep Calm: The Resonance of Technology and Art

Stepping out of the operating theater, Yang Zhigang inhabits a spiritual world defined by striking contrasts.

He is an avid enthusiast of calligraphy, particularly fond of copying the scripts of Wang Xizhi, the Sage of Calligraphy. In his eyes, the varying shades of ink—thick, light, dry, wet—and the fluid, sweeping movement of the brush share a profound principle with the rhythm he feels when manipulating micro-guidewires and packing coils during interventional surgery.

“In the black-and-white world of calligraphy and the black-and-white world of interventional fluoroscopy, I feel the same pulse,” Yang reflects thoughtfully. “The instant the brushstroke is made, that realm of ‘unison between heart and hand’ feels exactly the same as when a guide wire navigates a blood vessel. I believe this is a form of artistic and aesthetic cultivation. Once your aesthetic sense is elevated, you perceive more refined details in your work.”

Beyond the traditional “Four Treasures of the Study” (brush, ink, paper, and inkstone), Yang also persists in practicing combat sports (boxing/kickboxing). This ability to switch between “moving as swiftly as a fleeing rabbit and remaining as still as a meditative sage” has honed the most crucial quality for a surgeon: a sense of rhythm. It allows him to always maintain his own pace, refusing to be swept up by the external “rat race” of hyper-competition.

Yang also brings this wisdom of “balance” into scientific research and innovation. Currently, he is collaborating with the Center for Excellence in Brain Science and Intelligence Technology (CEBSIT) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences to develop a “High-Performance Interventional Brain-Computer Interface.” This is a disruptive innovation in the implantation of “ultra-flexible neural electrodes.” It requires only a single needle puncture into a blood vessel to deliver electrodes thinner than a hair deep into the brain to read signals with high precision.

Compared to traditional open-craniotomy implantation, this technique is less invasive, offers easier access to deeper brain tissue, and potentially allows for the implantation of electrodes in multiple locations during a single surgery. Yang is full of confidence in the future of this technology: “As engineering capabilities improve and material science challenges are resolved, this pathway via natural body channels will always be superior to creating new paths by destroying tissue. In the future, it will not only treat paraplegia but also play a major role in treating Parkinson’s disease, depression, and even tumors.”

Despite standing at the forefront of technology, Yang’s mindset is as peaceful as a hermit. He advocates the philosophy of Wang Yangming, specifically the concept of “cultivation through practice” (Shang Shang Lian). He views the trivial administrative work of medicine as a form of spiritual practice). He believes in “achieving great utility through a mind without intent” (Wu Xin Sheng Da Yong); he does not excessively chase worldly standards but rather follows the natural flow, doing his best and leaving the rest to fate.

Yang’s public science education account is named “Just Right” (Gang Gang Hao). This name runs through his medical logic and life philosophy: science popularization should not seek volume, but should “just right” resolve anxiety; surgery should not seek extreme visual perfection, but should “just right” benefit the patient; life should not seek immense wealth, but should “just right” fulfill one’s wishes.

At the conclusion of the interview, Yang said: “In conduct, action, and scholarship, a doctor must possess both benevolence and skill, constantly striving for improvement. I hope that future treatments for cerebrovascular diseases and even neurological conditions as a whole will be simpler, more minimally invasive, and safer.”

Interview

ShanghaiDoctor.cn: Regarding the “High-Performance Interventional Brain-Computer Interface” and “Endovascular Implantation of Ultra-Flexible Neural Electrodes” you are researching, what is the core advantage compared to Elon Musk’s (Neuralink) pathway of “drilling a hole” in the skull?

Dr. Yang Zhigang: The core philosophy lies in the belief that “utilizing natural body channels is always superior to creating new paths.” Any living tissue is nourished by blood vessels. Theoretically, as long as engineering capabilities meet the standard, we can reach any deep region of the brain through blood vessels, much like navigating a ship.

This approach is not only extremely minimally invasive but also possesses the potential for “one access, multiple destinations.” We may be able to place electrodes at multiple targets in the brain through a single vascular incision, without needing to drill holes all over the skull. Furthermore, for operations on deep brain tissue, the vascular pathway is shorter and causes less damage than the open-skull route.

ShanghaiDoctor.cn: If someone nearby suddenly collapses from a suspected stroke, during the “golden minutes” of waiting for the ambulance (120), what is the most important thing ordinary people should not do?

Dr. Yang Zhigang: Absolutely do not take unnecessary actions, especially do not blindly feed the person water or medicine, to prevent aspiration (choking). If the patient’s vital signs (breathing, pulse) are temporarily stable, the most important thing is to keep their airway clear. You can turn their head to one side to prevent vomit from causing suffocation.

Unless the heart has stopped and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is required, blind handling, moving, or shaking the patient by a non-professional may actually aggravate brain bleeding or ischemic damage. At this moment, keeping quiet, observing vital signs, calling for help promptly, and waiting for professional rescue is the most effective way to protect them.

ShanghaiDoctor.cn: The current medical environment leaves many young doctors feeling lost. What advice would you give to these juniors who are currently writing medical records and ordering lab tests?

Dr. Yang Zhigang: I highly advocate the concept of “cultivation through practice” (Shang Shang Lian) from Wang Yangming’s philosophy of mind. Even if the day is filled with ordering lab tests and accompanying patients for examinations—tasks that seem trivial or even menial—they are actually processes that temper one’s character.

Since these tasks must be done, rather than generating “internal friction” through complaint, it is better to think about how to complete them most efficiently, and to learn to observe and derive meaningful information from them. When you learn to silence the inner noise and treat every small task as a form of practice, doing it with refinement, the rhythm of your growth will not be easily swept away by external disturbances.

Dr. Yang Zhigang: Many people think cerebrovascular screening is only for the elderly. What is the actual situation you have observed in clinical practice?

Dr. Yang Zhigang: This is a huge misconception. Many cerebrovascular diseases are congenital or cryptic; they lie dormant in youth but are often “silent” and imperceptible before they erupt.

I suggest that if conditions allow, regardless of age—even for young people in their twenties or thirties—everyone should undergo a head and neck vascular screening (such as CTA or MRA). Ordinary physical exams usually only include routine items. Without specific screening for cerebrovascular health, many “hidden bombs” like aneurysms and vascular malformations cannot be detected. Early screening, controlling risk factors, and monitoring indicators to meet standards are far more important—and effective—than remedial measures after the disease has struck.

Editor: Chen Qing @ShanghaiDoctor.cn

If you need any help from Dr.Zhang, Please be free to contact us at Chenqing@ShanghaiDoctor.cn

Dr. Yang Zhigang | The Art of the Healer: Between the Brush and the Brain

Dr. Cai Junfeng | Guarding Bone and Joint Health, Improving Quality of Life

Dr. Xu Xiaosheng|The Gentle Resilience of a Male Gynecologist

Dr. Shi Hongyu | A Cardiologist with Precision and Compassion

Dr. Zhang Guiyun|The Inspiring Path of a Lifesaving Physician

Dr. Chen Bin | Building the Future of ENT Surgery at Lingang,Shanghai

Dr. Yang Zhigang | The Art of the Healer: Between the Brush and the Brain

Dr. Zhou Qianjun | Sculpting Life in the Chest

Dr. Cai Junfeng | Guarding Bone and Joint Health, Improving Quality of Life

Dr. Cui Xingang | The Medical Dream of a Shanghai Urologist

Dr. Xu Xiaosheng|The Gentle Resilience of a Male Gynecologist

Dr. Shi Hongyu | A Cardiologist with Precision and Compassion

Dr. Zhang Guiyun|The Inspiring Path of a Lifesaving Physician

Dr. Jiang Hong | Bringing Hope to Vascular Frontiers

Dr. Huang Jia | A Journey of Healing "Breath"

Dr. Chen Bin | Building the Future of ENT Surgery at Lingang,Shanghai