Update time:2025-12-15Visits:3717

Dr. Zhang Guiyun

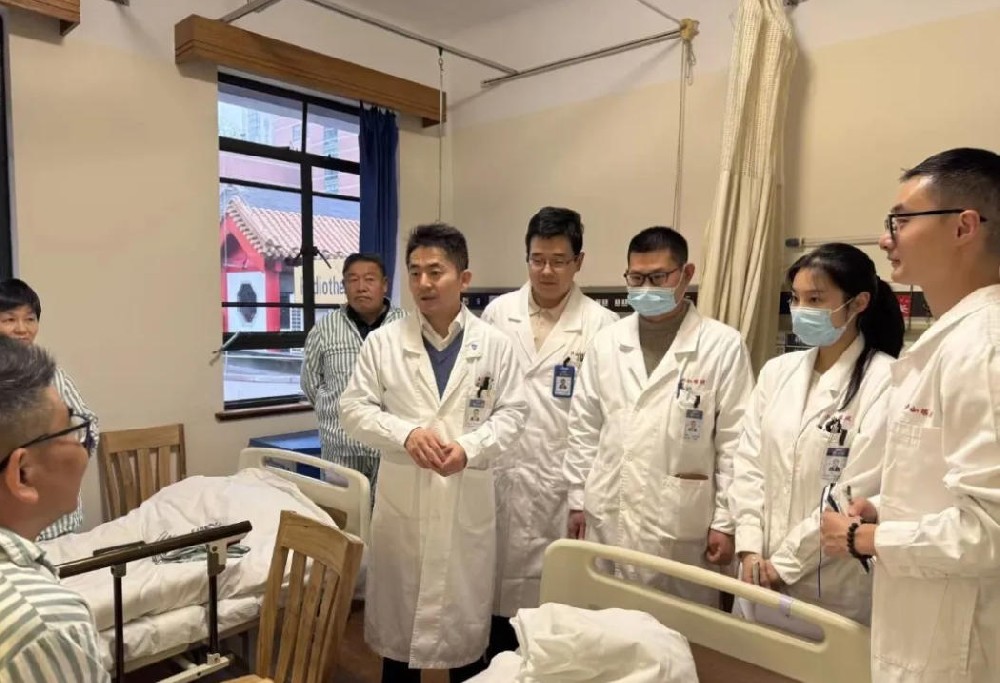

Zhang Guiyun, MD, PhD in Neurosurgery, Attending Physician. Deputy Administrative Director of the Cerebrovascular Disease (Neurovascular Intervention) Department at the Clinical Medical Center for Neurological Diseases, Shanghai General Hospital (Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine). Trained under Professor Ling Feng, a pioneering figure in neurovascular intervention in China. With more than 20 years of experience in interventional treatment of cerebral and spinal vascular diseases, he has developed extensive expertise in minimally invasive procedures for cerebrovascular conditions. He has performed over 5,000 cerebral and spinal angiograms and specializes in a wide range of interventions, including embolization for intracranial aneurysms, arteriovenous malformations, carotid-cavernous fistulas, dural arteriovenous fistulas, spinal vascular malformations, spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas, and perimedullary arteriovenous fistulas; stenting for carotid and intracranial/extracranial arterial stenoses; recanalization for various arterial occlusions (including carotid, vertebral, subclavian, and intracranial); and more than 3,500 thrombectomy and aspiration procedures for acute stroke. He is recognized internationally for his advanced work in interventional treatment of small- and medium-sized intracranial vessel stenoses. He was the first to use a microcatheter-delivered braided stent for venous sinus stenosis, achieving long-term stable results.

Introduction:

From a saline drip on a snowy winter night in a coastal city, to a blood donation needle on the high plateau of Golok; from millimeter-scale battlefields inside cranial vessels, to endoscopic explorations in the lab—he has spent more than two decades building bridges across the vast river of human lives.

He says, “Medicine is a journey with no final destination, but every life pulled back from the brink is the brightest star along the path.”

As the catheter snakes through blood vessels and verses quietly take shape beneath the heavy lead apron, what radiates from him is the purest essence of a physician: skill as the vessel, compassion as the oar—always the one holding the lantern steady in the rushing current of life.

The Saline Drip on a Snowy Night A Young Boy’s Promise to Life

The north wind hurled snow against the windows. It was a winter night in the late 1980s in a northeastern coastal city, and Zhang Guiyun still vividly recalls how, at age 13 and in his first year of middle school, his older sister’s sudden high fever plunged the whole family into despair.

Thirteen-year-old Zhang sat curled up on a long bench in the hospital corridor, clutching a borrowed English workbook. His pencil scratched across the faded pages, but his eyes kept drifting to the faint glow leaking through the crack in the ward door. Each drop falling from the IV bag felt like the second hand of a clock—or like the beads of sweat on his sister’s forehead.

“Fever of unknown origin”—that was the diagnosis the hospital offered, a helpless verdict that settled over the family like a boulder. For more than two weeks, they shuttled his sister between the county hospital and the city’s top academic medical center.

To this day, Zhang remembers his sister’s small, huddled form burning with fever, his parents’ trembling hands as they held the lab reports, and most of all his own crushing sense of powerlessness as he gripped that workbook: “I watched the fluid drip into her vein, drop by drop, but it couldn’t bring down that dangerous fever.”

By the time his sister was finally diagnosed with a rare condition, Zhang could recite every English word in the book from memory. The sharp smell of disinfectant, the steady beep of monitors, and his sister’s delirious murmurs in her half-sleep planted a simple but powerful resolve in the boy’s heart: “I want to learn how to heal people.”

“In that moment I understood that the longest distance in the world is the hand a loved one reaches out at the bedside, grasping for hope that feels just out of reach.”

When it came time for college applications, Zhang carefully wrote down three choices: China Medical University, West China School of Medicine, and Dalian Medical University. In the end, fate guided him to China Medical University—a school steeped in a proud revolutionary history. In 1996, he walked through its gates to begin his studies in clinical medicine.

“My sister’s illness showed me that being a doctor isn’t just a career—it’s like throwing a lifeline to someone teetering on the edge of a cliff. The thought alone feels profoundly meaningful,” he reflected years later.

After five demanding years, he pursued further training at Fudan University’s Shanghai Medical College, specializing in neurosurgery. Upon earning his master’s degree, he briefly returned home. But within months, drawn by greater opportunities, he headed back to Shanghai and joined the Cerebrovascular Disease Center at Tongji University under Professor Ling Feng. During his PhD interview, the young doctor’s eyes burned with determination: “I want to make an impact in ischemic cerebrovascular disease.”

When Professor Ling recounted her journey to France in the early 1980s to learn neurointervention—a field virtually unknown in China at the time—Zhang felt something awaken inside him. “She described how she brought back those pioneering techniques like carrying a spark into the darkness. In that instant, I could see my own future: threading a needle through vessels measured in millimeters. It was completely captivating.”

Sculpting Life in Millimeters

The shadowless lights in the angiography suite blaze like daylight. Dressed in a 40-pound lead apron, Zhang Guiyun stands before the digital subtraction angiography (DSA) system. On the monitor, the patient’s middle cerebral artery is clearly visible—a clot lodged firmly in place. Holding his breath, he guides the microcatheter along the winding vascular path. The instant the stent opens, new life flows.

“Neurointervention is like walking through a jungle where a tiger could leap out at any moment,” he often tells his trainees, quoting a classic surgical textbook. “Every procedure is a walk on a tightrope, and patients agree to step onto that wire with you only because they trust you completely.”

He once treated an elderly patient with atrial fibrillation who arrived with right-sided paralysis, a drooping face, and eyes filled with terror. The therapeutic window was closing fast—every minute lost meant nearly two million brain cells gone forever.

The microcatheter reached the clot. The retrieval stent deployed slowly. Zhang’s gaze stayed fixed on the screen, sweat forming at his temples: “During those five minutes, your heartbeat seems to duel with the monitor’s beeps. You hope the mesh will grab the clot firmly, yet fear it might tear the delicate vessel wall.” Quietly he adds, “At that point, doctor and patient are both taking a calculated risk—on anatomy, on device control, and on a little grace from above.”

As the stent was carefully withdrawn, a dark red clot sat perfectly captured in the mesh. The room fell so silent you could hear breathing. Almost at the same moment, the patient’s stiff right fingers twitched on the table.

“When the clot comes out, the patient can often move again right away. Six days later, this man walked out of the hospital. He turned back to us with the biggest childlike grin.”

Behind these “miracles” lies preparation most people can’t imagine. Before every complex case, Zhang mentally rehearses every detail: “Three-dimensional vascular anatomy, clot consistency, possible blind alleys—everything runs like a movie in my head.” The night before major surgeries, sleep rarely comes: “It’s not fear of failing; it’s fear of not being thoroughly prepared. Patients entrust us with their lives—we have to anticipate every scenario.”

Over two decades, he has performed more than 5,000 cerebral angiograms and over 3,000 interventional procedures. Those numbers represent countless sweat-drenched hours under lead aprons, 3 a.m. bites of cold bread in the locker room after long cases, and the indescribable rush of joy when a patient recovers.

“After one aneurysm procedure, a family member suddenly dropped to their knees in gratitude. I knelt too. As I helped them up, I saw a light in their eyes—not hero worship, but the pure shine of a life reclaimed.”

An Ark of Life at 14,000 Feet

In late summer 2024, when the plane touched down at Golok Airport, Zhang Guiyun felt the thin air for the first time. This cerebrovascular specialist, long accustomed to working beside Shanghai’s Huangpu River, grew winded after just a few quick steps. A pounding headache gripped his temples, yet looking out at the endless mountain ranges, he remembered the lighthearted verse he’d written before leaving: a playful rhyme about trading the comforts of the east for the high western plateau, parting from family, and embracing a new calling far from home.

Building a stroke center at Golok Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture People’s Hospital meant starting from scratch. No DSA equipment, no standardized acute stroke protocols, not even a dedicated team.

“Creating a stroke center here is like trying to grow crops in permafrost,” he said. Zhang worked alongside younger doctors to plan the space, calibrate equipment, draft workflows, and run simulations. Altitude sickness worsened his insomnia, yet he was always the first on site each morning.

On August 22, 2024—his 21st day in Golok—his body still hadn’t fully adjusted. Late that night, an urgent message flashed in the work group: a car accident victim with a ruptured spleen, O-type blood critically low. Before the pleas finished echoing, Zhang was already running to the blood bank: “I’m O-positive—take mine!” The nurse hesitated at his bluish lips, but he rolled up his sleeve: “First time donating at altitude, but saving a life matters more than anything.”

As blood from the banks of the Huangpu flowed into the bag, Zhang thought only of the young Tibetan man fighting for his life after the crash. The next morning, he checked on the patient, now out of danger and offering repeated thanks in Tibetan.

“It meant a lot,” Zhang later recalled. “In that young man’s eyes, I saw gratitude and renewed hope.”

Greater challenges followed across the vast pastoral region. As part of a medical aid team led by Director Zhou Xiaohui, over three years they carried out a “Healthcare and Education Across Golok” initiative, visiting nearly 40 townships and reaching close to 150,000 local residents and students.

“Practicing medicine on the plateau teaches you what true equality of life really means.” He remembers a civil servant from another province paralyzed by a stroke. With the DSA not yet operational, Zhang promptly administered intravenous thrombolysis. “Fifteen minutes after the drug, the patient could move again. When we transferred him to Xining, he gripped my hand and said, ‘I never thought I’d get a second chance at life here in Golok.’”

Looking at the thank-you banners on the clinic walls, Zhang reflects, “Behind every banner is someone who made it—healthy people of Golok, living full lives.”

Starlight in the Vessels Illuminating the Darkness

On the lab dissection table, a segment of isolated carotid artery gleams like pearl under the lights. Zhang Guiyun carefully advances a novel endoscope into the vessel lumen. On the screen, yellow plaque juts from the wall like submerged reefs—this is one of countless experiments in his pursuit of “visualized minimally invasive vascular surgery.”

“Traditional intervention is like embroidering blindfolded, relying solely on X-ray shadows,” he explains while adjusting the lens. “If we could directly see inside the vessel, it would be like giving the surgeon perfect vision.” The idea first struck him a decade ago during a difficult stenting case, when he suddenly imagined shrinking to microscopic size to navigate the path himself.

In 2018, he began endovascular endoscopy experiments on animal models. When the scope first reached the carotid bifurcation, the team erupted in excitement: “Inside a 7–8 mm vessel, we saw a whole world—shimmering plaque, floating intimal flaps, endothelial reflections!” Reality soon tempered the thrill—current tools could only look, not treat. “It’s like handing someone a telescope but forbidding them to reach for the stars,” he laughs. They tried laser ablation and miniature clamps, but miniaturization remained the bottleneck.

The real breakthroughs came at the bedside. In 2016, a patient suffering dozens of daily transient ischemic attacks (mini-strokes) pleaded for help: “Numbness hits me over and over—medications aren’t working. Please save me!”

At the time, no successful distal vessel stenting cases existed worldwide. After sleepless nights studying angiograms and MRIs, Zhang decided to place a laser-etched stent in the far reach of the posterior cerebral artery’s P2 segment. “During the consent discussion, I was upfront: this could be the world’s first, and there’s a chance you might not leave the table.” The patient replied simply, “Dr. Zhang, I trust you.”

The moment the stent deployed precisely and flow resumed, everything changed. As anesthesia wore off, the patient exclaimed, “The numbness is gone!” Six-year follow-up shows the vessel remains open.

“Medical innovation isn’t a lone hero’s tale—it’s doctor and patient standing back-to-back against the unknown,” Zhang says, flipping through the chart. “That patient’s ‘I trust you’ carried more weight than any guideline.”

He took similar bold steps in treating venous sinus stenosis. Facing a lack of dedicated stents, he adapted braided ones creatively. “Venous walls are paper-thin; standard arterial stents feel like rusty armor pressing painfully.” Showing the refined design, he notes, “We reduced radial force and improved deliverability. Dozens of patients followed for four years show no restenosis.” Today, domestic venous stents are in clinical trials, while his lab quietly advances combined endoscopy and flow-diversion systems.

“Every advance in medicine owes something to patients’ courageous choices.” That mutual support between physician and patient also shaped his venous sinus work—finding alternatives when rigid carotid stents caused headaches, validating a novel braided approach through rigorous cases.

“Bedside problems spark innovation, which loops back to engineers. That rapid cycle is the secret behind China’s rise in neurointervention.”

This quiet legacy traces a journey from following global leaders to running alongside—and sometimes ahead. From early pioneers adapting coronary stents for aneurysms, to homegrown devices outperforming some international brands; from importing techniques to publishing original Chinese protocols in top journals and presenting innovations worldwide. Trailblazers like Professors Ling Feng, Ma Lianting, Wu Zhongxue, and Li Tielin lit the way for the current generation.

Poetry and the Scalpel A Soul’s Refuge Beneath Lead

Late at night in his Golok dormitory, stars blanket the vast plateau sky in silence. Zhang sets aside his operative notes and writes in his journal a short poem about snow welcoming spring and flowers blooming in turn. Over his year of service in Qinghai, this surgeon—confident and precise in the OR—penned more than a dozen poems capturing moments of high-altitude medicine.

“Writing poetry isn’t about elegance; it’s a way for the soul to breathe,” he says, turning yellowed pages. “After a tough resuscitation, back at base, words just come. Verses feel like oxygen up here.” The lines celebrate Qinghai’s stunning beauty, reflect concern for rural healthcare gaps, and express awe at life itself—along with the unyielding spirit of today’s medical aid teams: “Catheter as bowstring plucking life and death, lead apron as armor shielding humanity.”

This poetic refuge grows from his deep thoughts on what makes a good doctor. Asked for his standard, he pauses: “Technique is the skeleton; humanity is the flesh and blood.” In his view, a physician’s true value lies not only in conquering complex disease but in broader health education for all.

“I can perform thousands of procedures and help thousands of people directly. But one public education talk can reach tens of thousands.” He shows short awareness videos on his phone. “Prevention means fewer people ever need to face the operating table.”

Zhang always explains conditions in everyday terms: “Think of blood vessels as pipes, plaque as buildup, and a stent as a spring that clears the blockage.” Once, after an elderly Tibetan woman understood, she offered him a traditional khata scarf: “Doctor, your words warm the heart like butter tea.”

Back in Shanghai, his clinic is always packed—many patients referred by former ones who say, “Dr. Zhang examines you like he’s catching up with an old friend.”

Facing the rise of AI, he remains open-minded: “AI can analyze molecules, speed drug discovery, even predict stroke risk. But no machine can replace the warmth when a doctor holds a patient’s hand.” He’s already exploring AI for stroke early-warning systems: “Imagine a phone app monitoring high-risk people in real time, like a sentinel watching the weather on the plateau.”

“If disease were eradicated, what role would doctors have?” A spark of longing lights his eyes: “That would be medicine’s greatest triumph—an old saying goes, ‘If only no one fell ill, why worry about dust on the pharmacy shelves?’” Then he smiles. “But if that day comes, I’d probably write a book of poems chronicling ordinary people’s epic struggles against illness. That, too, would be worth it.”

As in one of his Qinghai poems: “Hoist sail from Shanghai bound for Qinghai, strike the oar midstream to shatter the waves. When osmanthus fragrance fills Shanghai again, the curved blade will gleam along the Pujiang once more.”

This beam of starlight within the vessels will ultimately light many more nights of human life.

ShanghaiDoctor: Dr. Zhang, you’ve mentioned how rapidly domestic medical devices are advancing in neurointervention here in China. What are the key factors driving this progress?

Dr. Zhang Guiyun: It really comes down to the broader momentum of our country’s development. Homegrown companies have sprung up like mushrooms after rain, and some of their design concepts now surpass international ones. The biggest advantage is localization—we clinicians can sit down one-on-one with engineers and give them direct feedback on challenges we encounter in the operating room. Manufacturers respond quickly and refine the devices. For example, we used to rely entirely on imported stents; now domestic ones are far more adaptable to our specific clinical needs. This fast iteration cycle has fueled tremendous growth in the field. More and more Chinese researchers are publishing original protocols in the world’s top journals, and the global community is starting to hear our voice. That said, cerebrovascular disease remains the number-one killer in China—high incidence, high disability, high mortality. The task ahead is still daunting. Beyond procedures, we need to focus on public education so people can prevent and treat issues early, ultimately easing the burden on our healthcare system.

ShanghaiDoctor: In your treatment of venous sinus stenosis, you were the first to use a braided stent. Why did you decide to adapt a stent originally designed for another purpose, and how did you manage the risks?

Dr. Zhang Guiyun: Early on, there simply weren’t any dedicated venous stents available, so we had to use carotid stents instead. But those were engineered for arteries—they were too stiff, difficult to deliver, and often caused severe postoperative headaches. Faced with that limitation, and after fully informing patients and obtaining consent, we cautiously explored alternatives. Through careful theoretical modeling, we selected a braided stent with more flexible radial force. The results were remarkable: long-term follow-up on dozens of patients showed no restenosis and complete resolution of pain. Innovation in medicine can’t involve reckless trial and error—patient safety always comes first. Yet when patients have no other options, we have a responsibility to search for new solutions within safe boundaries. Today, companies are actively developing dedicated venous stents. That’s a perfect example of how clinical needs drive progress: doctors identify the problem, engineers respond, and ultimately patients benefit.

ShanghaiDoctor: With the rise of AI, how do you see it transforming neurointervention? What will the relationship between doctors and AI look like?

Dr. Zhang Guiyun: AI is going to bring disruptive change. Take drug development: in the past, analyzing protein structures was exhausting and slow; now AI can dramatically speed up the discovery of new medicines and even help manage chronic conditions like hypertension and diabetes with long-acting treatments. For neurointervention, that’s actually “competition”—if diseases are caught and controlled early, we might have fewer patients needing procedures. But that’s a wonderful thing! It aligns perfectly with the Healthy China 2030 vision. Doctors should embrace AI with open arms. It empowers us—for instance, we’re working on stroke early-warning systems that use smartphone apps to monitor high-risk individuals in real time. Still, AI will never replace the warmth of a doctor holding a patient’s hand. Lifespans may extend to 120 years someday, bringing new challenges, but with generations of physicians and engineers working together, I believe we can move closer to that ancient ideal: a world where no one falls ill.

ShanghaiDoctor: Your workload is enormous, and you’ve spoken about insomnia and stress. How do you cope? I’ve heard you enjoy writing and music.

Dr. Zhang Guiyun: You have to be mentally resilient to survive in this profession. Normally I can fall asleep the moment my head hits the pillow, but before major cases I often lie awake—not because I’m afraid of failing, but because I’m worried I haven’t prepared thoroughly enough. I keep replaying every step in my mind. Hobbies help me unwind. Sometimes, in the middle of deep thought, inspiration strikes and I’ll jot down prose or poetry. I’ve even used AI to compose music. During my year of medical aid in Golok, living alone in a simple dormitory, I spent quiet evenings observing the plateau landscape and writing poems—now I have more than a dozen. Writing poetry isn’t about being refined; it’s about giving my soul a way to breathe. After a tough resuscitation, when I’m back in bed at 3 a.m. and sleep won’t come, putting a few lines on paper feels good. Those verses are like oxygen on the high plateau—they let me catch my breath. These interests help me find balance amid the intense demands of the job and keep my reverence for life intact.

Editor: Chen Qing @ShanghaiDoctor

If you need any help from Dr. Zhang Guiyun, please be free to let us know and email us at chenqing@ShanghaiDoctor.cn.

Dr. Yang Zhigang | The Art of the Healer: Between the Brush and the Brain

Dr. Cai Junfeng | Guarding Bone and Joint Health, Improving Quality of Life

Dr. Xu Xiaosheng|The Gentle Resilience of a Male Gynecologist

Dr. Shi Hongyu | A Cardiologist with Precision and Compassion

Dr. Zhang Guiyun|The Inspiring Path of a Lifesaving Physician

Dr. Chen Bin | Building the Future of ENT Surgery at Lingang,Shanghai

Dr. Yang Zhigang | The Art of the Healer: Between the Brush and the Brain

Dr. Zhou Qianjun | Sculpting Life in the Chest

Dr. Cai Junfeng | Guarding Bone and Joint Health, Improving Quality of Life

Dr. Cui Xingang | The Medical Dream of a Shanghai Urologist

Dr. Xu Xiaosheng|The Gentle Resilience of a Male Gynecologist

Dr. Shi Hongyu | A Cardiologist with Precision and Compassion

Dr. Zhang Guiyun|The Inspiring Path of a Lifesaving Physician

Dr. Jiang Hong | Bringing Hope to Vascular Frontiers

Dr. Huang Jia | A Journey of Healing "Breath"

Dr. Chen Bin | Building the Future of ENT Surgery at Lingang,Shanghai